Parkside Memories, 1959 to 1989

Stuck in the Shaft

This was one incident worthy of recalling, it was one day as we were going underground on the afternoon shift. There had been a pretty violent storm on the surface, and water had cascaded into the powerhouse getting into the bus bars. We were halfway down the shaft, when the cage just stopped dead! For a few minutes everyone was quiet, waiting for the cage to start to descend again, but it didn't. There were three decks of men in the shaft, and each deck held 30 men. Inevitably there was the usual banter about being paid for "hanging around "!

The delay went on for another three quarters of an hour, by which time some of the men were beginning to panic a bit. Eventually the emergency system was brought into being, and this was quite simple really. The brake on the winding drum failed to "full on" when the current went off on the winding engines, so as the counterweight was heavier than the cage, it was only necessary to free the brake to allow the cage to freewheel back to the surface. There was a diesel generator installed to provide emergency power for this purpose, and the delay had occurred due to the fact that there was no diesel to start this up! Everyone in the cage was allowed to go to the canteen for a drink, but some of the men decided to call it a day and they got changed and went home.

L19/ L40 Development

When the face was being developed for L19, it was found that there was insufficient air to ventilate it properly. We were always getting a build up of gas, so it was decided to make a parallel return for L19. This was accomplished by utilizing the old roadway, which had been L40 face. This face was one that had been worked from the north side of the pit. There had been heating problems on it with the result that it had been flooded and abandoned.

Although the seam was the same, due to faulting, there was a difference of about 50yds in the levels of the coal. This had to be tunnelled through before a connection could be made. The NCB workmen drove a tunnel of about 150yds through the fault before the job was handed over to ATC, and I did some firing in this tunnel myself. When we were 20yds from the breakthrough point we dropped down from 16x17x12 arches to a small size of 6x6. We had to proceed then with extreme caution, because we were coming to something unknown. There was a possibility of flooding, also a large volume of gas, maybe even carbon monoxide.

The men went forward using jigger picks, until we were within 6ft of a break through. Then a hole was drilled to tap off the gas. A tube was fitted in the hole, with a tap attached to monitor the gas flow. At first there was 100 per cent methane coming out. It was monitored for CO by using Draeger tubes, which are small glass tubes filled with a compound that turns black in the presence of CO. Happily we found none. The water was bled off the same way as the gas. As the percentage of gas dropped, extreme care had to be taken when the "Explosive Triangle " was reached. This is when a gas and air mixture is at its most volatile. It is in the range of 7.5 - 20%.

Breakthrough point L19/40.

As soon as the area was declared safe, a small exploratory hole was cut through, about 4ft high and 3ft wide. Jack Ellis the overman was the first to go through, or at least he thought he was. We had a very irresponsible lad working at Parkside, by the name of Raymond Cunniffe, He was in this roadway, working as a haulage lad, the barrier had just been breached, and Jack was waiting until some fresh air had been circulated. Jack had gone out of the roadway for something or other, so Raymond, seizing his chance, goes through the gap to be the first to go into the "unknown". Jack knows nothing about this, and comes back with Jim Wormwell, the deputy manager in tow. Jim says to Jack."Have you been through yet " "No" says Jack," I'm just waiting for the air to clear a bit". To which Ray pipes up "I've been through, it's OK" Jack was furious!!

I went through myself later on. All the arches and timber were festooned with mould and other forms of fungi. It was sweaty and humid. The roadway, once opened up, had to be cleaned up of debris that had fallen from between the arches when the roadway was under water. As always at Parkside, everything was done in a hurry. There was no time to lay track, we had to transport everything along the bottom belt. Considering the state of the roadway, this was quite hazardous and not very practical.

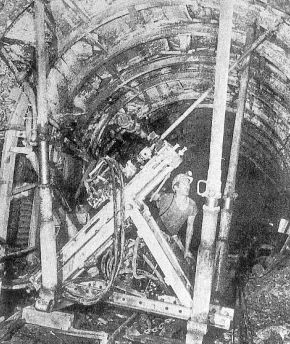

This was typical of conditions in L40.

The existing roadway can be seen as a small hole to the top of the picture and bottom right is the top of the EIMCO loading bucket.

Near the top of the tunnel we had to install air doors to make a booster fan station to house a 40ins fan. This was necessary to pull enough air through for L19 face. I was in charge of L40 for quite a spell. The supplies system was appalling. Supplies were sent down E3 brow on the rider, and then taken into L19 level. When empties were brought out of L19 return, they were shunted towards L40, and only cleared at weekend, thus creating a bottleneck. Any supplies that were needed for the job in L40 had to be sent along the bottom belt. Sandbags, stilts, struts, arches. They were all sent in this way.

One day Bert Dyer the manager came into the district, he decided that the answer was a "slusher" I couldn't see the point of one myself. I'd seen slushers before and they never gave a very satisfactory answer. We had to remove all the belt structure to get it into the job, and finally it was in position and working. It never came up to expectations, and finally it was put on one side and forgotten about. I got moved out of L40 soon after that and I was glad to see the back of it. I went on to L19 and I stayed there for the rest of my time underground, more or less.

The Manrider Incident

A bizarre incident occurred one holiday time, concerning the manrider, which ran down the E 3 brow. I was a deputy at the time, and the practice was to start all the belts and leave them running for the preceding shift to ride out. We were only on for travelling and safety, and there were just deputies and travellers who wanted a ride out. The manrider was in operation for the dayshift only, and the engineman finished work before the men that we were relieving had come out of the districts. I climbed aboard the rider and knocked him away. When I reached the first transfer point, I stopped the rider and got off, never thinking to put the latch on the signals, after all, there was no one else about, as I thought, to knock him on again.

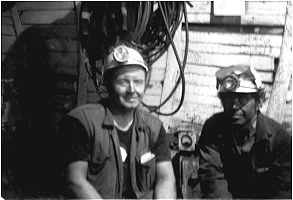

As I was going around the front of the train, to start the belts up, it moved off, brushing past my leg. If I had been a second later I would not be writing this, as I would have been crushed to death under the carriages!! I found out later that an electrician had come into the district from the north side of the pit, via L40, and had knocked for the rider to go down brow, knowing nothing of the fact that I was using it. During the Christmas holidays of 1980, I took my camera down the pit and managed one or two photos taken using the cap lamp as illumination. These are two of them taken at the sub station opposite the L16 entrance. Bernard Butcher and Frank Groves were with me at the time.

The Buckshot Accident

I was working one weekend in March 1980 in L19 main gate when in incident occurred. We were using a "Buckshot" machine. Let me explain, this preparation known, as buckshot was a mixture of cement and grit, which was directed from a hopper into a 2ins pipe, and blown along to the muzzle of the gun from which it was ejected. It was blown along the pipe as a dry mix, and when it was 6ins from the end of the gun muzzle, a jet of water was mixed with it, and the resultant mixture blown onto the pack side to seal any holes that had been left. This was to combat spontaneous combustion. The mixture would set pretty quickly and could be sprayed over again to form a thick layer. The two men working with me were Harry Wilding and Vinny Snaylam. The gun blocked up, and Vinny went to clear it. As he was doing so, the buckshot suddenly shot out and hit him in the eyes. He was blinded by it and couldn't see anything. Harry was carrying a water bottle for a drink at snap time, as luck would have it, and we used this to wash out Vinny's eyes. Vinny was extremely fortunate that Harry had some water; otherwise he could have lost his sight. As it was, he lost some vision but not a lot. It could have been a lot worse.

One man who did lose an eye underground, however was John Else. It was a bizarre accident in March 1979 Let me explain the circumstances that led to it. Boreholes were periodically drilled down from the surface to prove the reserves of coal. When these were completed, they were filled with concrete, to seal them up. Unfortunately one of them had not been completely filled and an accumulation of gas had gathered in it. This gas was under quite a considerable pressure and as the face advanced to it the pressure build-up blew out with force, and the coal hit John in the face, doing permanent damage to one of his eyes.

I worked on the face at L19 for quite a long spell, some of it as shotfirer but mostly as deputy. Derek Shaw was the overman and Jack Johnson the shotfirer. As L19 was being developed, we found a fossilized tree branch, about 4ft long. We couldn't get it out in one piece and it was taken out in pieces by various men for their children to look at. The cuttermen on the top machine were Jimmy Shea, Tommy Woodacre and Jack Dawber. Jack was also known as "Pink Panther" from the fact that he was always humming the theme tune! He took a prodigious amount of snuff every day, and this he kept in a box in his helmet.

Methane gas boring rig.

We had loads of problems on this face due to gas. When the cutter was going up the face, the gas output was quite high, and we had to go to the outbye end of the return to monitor it. The legal limit was supposed to be 1.25%, but we have cut with up to 2.5%. It was about this time that L40 was put into the ventilation system, giving the extra air that was needed. Methane drainage was carried out on every face at Parkside, using the boring rig in the picture. Holes were drilled up into the waste area and also down into the floor, 2" pipes inserted into them and the gas drawn off into a range of 10" pipes. Without this system, the Florida seam could never have been worked. We had a rider system in L19 return, which worked very well. In fact the whole of the personnel of the face travelled in on the system. We managed to keep the return open by means of a couple of teams of dinters, who would fill the dirt into bags and put it in the empties as they were being taken out. The face itself ran for 2500yds and was replaced by L30 and L31.These were the last faces to be worked in the Lower Florida at Parkside, as floor heave and side pressure made the seam uneconomical to work.

The AFC on L19 was a heavy duty one, due to the amount of coal that was coming off it, in fact, everything on L19 was heavy duty. I reckon that it was one of the most productive faces that ever was worked there. All told I estimate about 2million tonnes of good quality coal came from that face. Finally it was so far in that the roadways had to be signed for by another deputy, as the distance was too great to be travelled in the time allotted by one man.

My last shift on L19 came in January 1981. It was an afternoon shift, and I was deputy in charge. I was travelling on my rounds inspecting the district, when I came across the return haulage men. They were short-handed, so I gave them a hand, literally, as it turned out. They were taking a 10ins pipe, on a tram to the end of the gas range, and I gave them a hand with it. As we reached the end of the rails, the tram front wheels dropped off the rails, and the back end of the pipe shot into the air with my hand on the pipe flange. Unfortunately my thumb was trapped between the C.A. range and the pipe flange, breaking it in four places and requiring eight stitches. I spent the next 8weeks at home on the sick list. Just about the same time Brian Waring broke his leg in the main gate when a dowty prop sprung out. That was a nasty one too. A compound fracture of tibia and fibula. Brian finished up in Warrington Infirmary, as an in-patient and he was left with one leg shorter than the other. It was about the time that entonox was in general use underground and Brian was full of praise for its effects.

When I finally started back, someone else had taken the job on L19. I did a bit of work in the strata bunker that was being built off L18 brow. Joe Sockett had gone off work with ill health, and his job as Materials Officer was up for grabs so I put in for it, and was fortunate enough to get it. The last shift that I actually worked as an underground official was on a Saturday, and it was the day that Bill Tickle the rope man broke his neck. It was a bizarre accident that could have happened to anyone. Bill was passing under a series of low girders, he ducked under the first and came up on the second, twisting his neck awkwardly. He finished up a quadriplegic. After a long time in physiotherapy, he regained some use in his limbs, but he never worked again.

Continued...