Parkside Memories, 1959 to 1989

A Shotfirer Again

When my training was complete, I was given the stable end to fire each day. The stable end had to be kept in advance of the face, as this was to allow the shearer to come in while the face conveyor was pushed over. It was just the cutting disc that came into the stable, and as the panzer was pushed over into the new track, the disc was in position to cut into the newly exposed coal.

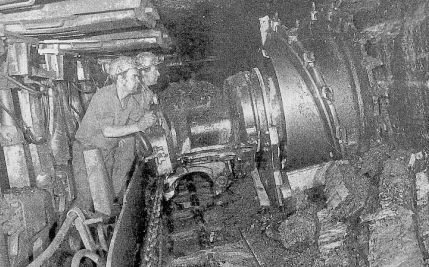

A Ranging shearer at work.

The shearer had a hydraulically operated boom and a cowl, which had to be thrown over when the cutter was ready to go up the face again. The cowl was to stop the cut coal being left in the track behind the machine, thus, when the machine was going up, cutting the tops, the cowl was dragging behind the machine in the track being left as the coal was cut. When the cutter reached his changeover point, the cowl was pulled over to the opposite side of the disc, the boom lowered and the disc then cut out the rest of the seam as the cutter came down the face again.

To throw the cowl over was a work of art. It was done with a piece of chain, which had a hook at one end. It was just a short piece about 2ft long. The hook was fixed onto the cowl and a link put on a pick in the disc. The cutterman then flicked the machine on and off, and the cowl was over. There was always about 9ins of coal left in the roof as a support as the natural roof was rather friable. The face was only supported at each end. Here, dirt packs were built, about 6yds long, the walls being formed with sandbags, filled with loose dirt, and the middle filled with dirt from the ripping lip.

Usually the waste edge was supported by stacks built from pieces of wood, about 2ins square, and 2ft long, built domino fashion and filled with loose dirt. This timber was known as "pillarwood". The rest of the roof was caved in behind the chocks. Actually the amount of roof that fell was a thickness of 4ft. Above this was another seam of coal, the Higher Florida. This tended to bend, and slowly come down to meet the floor about 30yds back in the waste. With all this amount of combustible material in the waste, there was always a chance of a heating. The way that this was combated was to blind the side of the roadway with "hardstop", a gypsum based compound, and when mixed with water and smeared on the covering boards, it formed a seal to stop any air being drawn through the waste, because heating is caused by the slow movement of air over combustible material.

The face used to advance at a faster rate than the ripping. The cutter could make 2 runs each shift, making a total advance each shift of 5ft. The rippers would each do a "cycle" i.e. One complete arch set. As the arches were set at 3ft centres, this gave a discrepancy of 2ft each shift. On a good week the amount of rip to be caught up was anything from 15ft upwards.

The problem was the way that the job was paid. Everyone had the same wage. This was known as PLA, or Power Loading Agreement. Thus, if one team of rippers did a cycle, the other team would do the same. What used to happen was that the ripping was done at weekend at overtime rate. Time and a half until 12noon Saturday, and double time for the rest of the weekend. The method of support for the ripping area was by means of 15ftx3''x3'' box section iron bars these were set at intervals of 2ft, and supported by dowty props. In theory the props and bars had to be withdrawn before the rip was fired, but this never happened. To fire the rip, it would take 10 shots, with three delays. A line of 5 across the middle, 3 more above these and another 2 at the top.

At the return end was a "feeder" AFC (armoured face conveyor), which was attached to, and delivered on to the face conveyor, and this was left running while the shots were fired.

This way, quite a lot of the debris was got rid of. The rest was filled out by means of the Eimco loader. These Eimcos differed from the ones that were used in the tunnels, as they were electrically powered. They had an electric/hydraulic system, and the bucket was a side tip. It was possible to fill out the spoil in less than an hour, if the conditions were right. As the bars and the dowty props were uncovered, they were dragged out into the heading by means of a chain, fastened to the bucket.

The arch crown was put into place while the dirt pile was still there, and then covered in with corrugated iron sheets. The struts that were being used at that time were made from angle iron, and bolted by means of a hook bolt into the web of the arch. The legs of the arch were put into stilts, which had friction plates to allow the legs to sink as the weight came on them when the face advanced.

While I was working as a shotfirer on L16, I was in the top road one day, giving the rippers a hand when I managed to break my thumb. I was holding a "jigger pick" i.e. compressed air, hand held rock breaker, at the time, and a piece of dirt fell and caught me on the thumb. Dickie Pilkington, who was deputy, said to me, "Hast'e'er done any actin'" When I asked why, he said "ah've never sin anybody poo so many faces us thee when tha geet that smack" There's not much sympathy down a pit!

Not long after this, I got the job as deputy on L16, as Benny Astley, the regular man had to go off work with a bad knee, and I took his place. Jack Atherton had dubbed Benny, "Dick Dastardly", after the cartoon character, because Benny had a large chin and a 'tache, and really looked like him! Jack was a brilliant poet and could make up rhymes about anything or anybody. He once made up a rhyme about Sid Hichisson and his prize onions, which had everyone in stitches except little Sid.

It was in L16 top road that I picked up a scar under my left eye. I was travelling towards the face one day, and there was a piece of lagging hanging down. The roadway at this point was low due to floor heave, and I walked into the broken board. I suppose that in a way I was lucky, the board could have gone into my eye.

As I have just said, the Lower Florida was a bad mine for floor heave, and we had tremendous problems with the return road especially, as we had no way of getting rid of the dirt from a floor "dint" (a Yorkshire expression for taking the floor up). L16 face ran for approximately 800yds, 500yds of which was catered for in the return by using L15 main gate as a return for L16 and making "sluice" roads every 100yds or so into the actual return.

For the last 300yds of the face's life, it was decided to try and manage without anymore re-ripping of L15, mostly because of cost. We tried bagging the dirt and packing it on the sides of the roadway, but gradually the roadway contracted. Finally we were left with a narrow gap to get the supplies in to the face. At the worst point it was 2ft 6ins high and 3ft wide. We had 3 trams made in the workshop. These had small wheels, and were coupled together by chains, their chassis having been lowered as much as possible to give maximum clearance.

There were three men given the job to get the supplies in. Bob Smith, Steve Morris, and Jeff Barker. They were allowed to work 2hrs extra each day to boost their pay, but I think that it was a bribe for the conditions. The inspector came one day, and when he saw the system, he made the management install a "green line" system so that the haulage could be isolated, if and when the trams came off the road. They did this quite frequently, and usually they de-railed in the very narrow part of the roadway. The only way to re-rail them was to crawl down the side of the trams and, using a lifting jack, get them back the track.

The clearance was so small that a 10ins methane pipe would just clear the roof. Finally, for the last 50yds of the life of the face, most of the material was transported up the face from the main gate, using the face conveyor in reverse.

About April 1976, when I had been shotfiring about 5months, I was a bit late getting down the pit one morning and the rider had left the pit bottom. I had all my powder to take in and didn't fancy a walk, so I asked the locoman if he would take me in on the back loco. Two locos were used to see to the manriding train, one hauled it inbye and the other followed it in to haul it back. This was because there was no way that the front loco could get to the other end of the train to haul it back. I got into the back cab of the loco with all my stuff and we set off.

We were going along the south tunnel and had just passed the 4ft bunker, when the brakes slammed on and the loco skidded to a halt. Terry the driver jumped out and shouted to me "We've hit somebody" I looked back along the track and saw what looked like a bundle of rags. We both ran back and found a man lying there groaning. When I looked at his foot, it was nearly severed! There was a first-aid station nearby, and we got a stretcher. I opened my first-aid tin that all deputies carry and bandaged his foot as best I could.

By this time Sid Hichisson had arrived and he administered morphine. We got the man on the stretcher and got him to the pit bottom, after I covered him with my coat, and he was taken up pit to the hospital. Terry and I had to wait for the inspector to arrive. I was freezing! The pit level was no place to be without a coat.

It turned out that the man was an electrician, Jim Lovatt, coming off nights, and he hadn't seen the loco until the last minute. The place that he was coming from was the opening to the Wigan 5ft seam and it was warm in there. As he came out on to the pit level, he put his collar up to keep the cold out and missed seeing the loco. He tried to avoid it, but his foot had gone under the footplate and had been twisted round like a carrot top. The loco driver was exonerated and the man came back to work after a while to work on the surface, having lost his foot and part of his leg. I spoke to him a few years later, and he told me that he didn't remember anything of the accident, except waking up in the hospital at Warrington. I was awarded a safety tie later on for saving his life by bandaging his ankle. Apparently he would have bled to death if I hadn't done it.

While I was working on L16 the job of Materials Officer became vacant. I thought that I might have a chance, having done it previously, 12 years ago, but it went on this occasion to Joe Sockett, a man who had transferred to Parkside from Ellington Colliery, in Northumberland. Joe had been an overman at Ellington, and had come to live in Burscough. I dont think that Joe was really bothered about working underground at Parkside, and the supplies job suited him. I found out about the rejection on the same weekend that Dad died.

Sometimes when there was a shortage of officials, I would be sent on to L18 face. What a dump this was! It was taking the coal on the lower side of L16. The usual officials on this face were Jackie Platt, and Arthur Whittle as deputy and overman respectively, plus a shot firer. I've never seen a face as bad as this one. I recall going there as a deputy one day when they were shorthanded. The main gate was a shambles; there was a pump in the heading that delivered water into a tank outbye. This was just "nuisance water" that accumulated there. While I was there the main gate Eimco that was used to fill out dirt from the rip, stopped in its tracks.

When I went to investigate, the cable coupler had fallen into the water tank, shorting it out. The men on that face didn't seem to be a bit concerned about anything. Drilling machines were lost regularly. They would be put on the seat of the Eimco and would fall off into the slurry that seemed to be always present on the floor, due to the wet conditions in the heading. I shudder even now to think of that face!

The face was being worked at an angle to the roadways, and this meant that every week or so, a chock at the main gate had to be transported along the face to the return end, to keep it in line. The way that this was done was to lift the chock onto the panzer, chain it to a flight bar, and with the conveyor in reverse, drag it along the face. This was ok as long as the chock didn't meet with any obstructions. If, by chance it caught on anything, the chain would either break or be stretched.

The chains that were used were the ones that the haulage men used to lash the carts to the rope with, consequently, after a weekend; the haulage was short of chains. This led to chains being stolen from other districts, which also meant that anyone who had a spare chain would hide it to stop this happening. It was a vicious circle.

This was L16 Main Gate after salvage.

We hit the step on L16 in December 1976. The men were then transferred to the development of L17, which was a short life face, taking the coal from between L16 amd L18. Some of the workforce was deployed to the salvage of L16 and I was in charge of this job. We had to remove all the chocks from the face, dismantle them, and send them up the pit for re-furbishment.

It was the first time that chocks had been salvaged. The usual practice was to leave them on the face along with the AFC and just salvage the motors from the drives, together with the cutters. It was a very wasteful practice, which was to be radically changed in the future. We sent the chock beams out on the belts, to the end of the level, and loaded the bases on to trams.

There was one incident worthy of noting during the salvage, when we had a runaway in the main gate. There were two men taking a tram in to pick up another chock, when the lashing chain became loose. The tram ran away for 300yds before becoming de-railed, just stopping short of a group of workmen. A bit ironic really, as we normally had problems keeping the vehicles on the track during normal haulage operations. I think that we salvaged more material from L16 face than from any other at that time. In fact, all that was left in when the seals were put on was about 300yds of track.

L17 Drivage, note ventilation tube to left.

The roadway that was to be L17 main gate was driven through the worked ground of L16, about 500yds from the entrance, and going off to the left hand side. When roadways are driven through the waste area like this they are known as "scours." One team of men started from L18 brow and the other team from L16. The surveying team was spot on with their calculations, as both roadways "thirled" exactly on line. After we had completed the salvage of L16 I was sent on to the development of L19, which was to be the longest running face in that particular seam. In fact it was still running when I took the job of Supplies Officer in 1981. It actually ran for over five years and went for over 2500 yds.

Continued...