Parkside Memories, 1959 to 1989

John Coffey and the Spillage

While I was working with Bob and Dick, word came to us to go to the entrance of L16 main gate and to take our spades with us. When we arrived there a solid wall of coal met us. Apparently there had been a spillage, and what a spillage!! The man in charge of the transfer point was John Coffey, a little man who was in his 60s. He had been a faceworker in the past, but as was the custom, when he could no longer work on the face, he was found light work.

He had been watching the coal as it came off the L16 belt and transferred on to the E3 conveyor. This can have a hypnotic effect, and the continuous rumble of the coal makes you dozy, and John had dozed off. He must have been asleep for quite a long time because the face had cut up and down twice, and all the shift's production was on the floor. As the coal had backed up in the chute, it started to spill off on either side of the belt head, which was 5ft from the ground.

It gradually spilled off further and further into the level until there was a pile of coal stretching back to the air crossing, a distance of 20 yds. JC, as John Connaughton was known, said, "That man does not go near a transfer point again!" I reckon that it took 2 days to shift it, and it took 10 men to do it.

I stayed with Bob and Co for a couple of weeks and then I was moved on to the afternoon shift to work with Arthur Wilkinson and Tommy Smart, who were re-ripping in L16 return. It was a hot place to work in, being the return, and we were stripped down to shorts for most of the time this roadway had been originally the main gate roadway of L15, but the pressure on it had been so great that the floor had risen up and had met the roof thus closing the roadway completely. The Lower Florida was a bad mine for this kind of thing. The entire flank faces off E3 never reached their boundaries, because crush conditions made it impossible to get supplies in to them when they advanced past a certain distance inbye. In fact in L15 main gate, as we re-ripped, we extricated pipes, belts, rails and all sorts of other material that had been left in after the face had finished. None of it was usable and it had to be sawn up and stacked up in an old roadway.

The actual L16 return was 15yds to our left, but was being crushed badly. As we advanced with the re-ripping we had to make a cut-through every 50yds to the return road. This was to enable supplies to be taken through for the face. By doing this re-ripping of the old main gate, L16 was the only face to hit the fault, and go to its full distance.

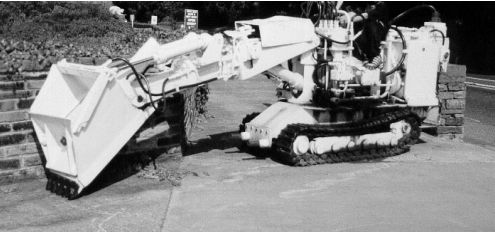

In the main gate road of L16 the floor heave was kept under control by use of a "Hausherr" dinting machine.

This picture was taken at the Yorkshire Mining Museum.

This was a track driven digger which had a long boom at the front end, and at the end of this boom was a digging bucket. The operator would take up about 4 length of track and then commence to dig down to the bottom of the arches to get to the original floor. Once he got himself established, he would carry on digging out and re-laying the track on the new floor level. The machine bucket had a unique feature, because, as it couldn't tip to empty, it had a plate at the back, which pushed forward to empty it. All the spoil went out with the coal, and the length of the boom meant that it could reach under the conveyor belt and so clean up all across the roadway without moving from its position in the haulage track.

I stayed with Arthur and Tommy until I had completed my CPS. By this time I had given up using the coach to get to work. It was too much of a dash at the end of the shift, because if you were a bit late getting changed, the driver would leave without you. However, there is a tale to be told about the coach. We had a driver by the name of Joe, and each Friday, we had a whip round for him. There was a man travelling on the coach, by the name of Tommy Atherton, otherwise known as "Doggy", and he had been in dispute with Joe over something or other. This particular Friday, Doggy said that he wasn't putting anything into the hat. It just happened that the man he was sat next to was Big Gordon, who weighed in at around 20stones. Big Gordon said to Doggy, "Are tha not payin'?" To which Doggy said "Nowe ahm not" Gordon said "Well then, tha're not gerrin off" It was a pantomime to see Doggy trying to get past Big Gordon that day! He finally managed it to the cheers of the other men on the bus!

After my re-entry training had finished I had a spell with Bob Scrivens, who was in charge of the conveyors. We were re-structuring the belts on E3 brow from L16 main gate down to L18, taking out 36ins structure and replacing it with 42ins. This had to be carried out while the belts were running, so 2 men had to work together on it. By this time I was picking up a bit of overtime as well, which didn't come amiss.

I had been back at the pit for about a month when I received word to go to Old Boston Training Centre to renew my gas testing and hearing papers, and to take the first aid exam, as this was the first step to becoming a deputy again. April 14th was the day in 1975 that I started at Boston. We had 3 days there on instruction and one day at St Helens Tech for the exam. I started back on the Friday afternoon shift and we had a pretty unpleasant job to do when we got underground that day. A man, Jack Taylor, was buried in some old workings at the top of E3 brow, and we were detailed to help dig him out. A covering board had come loose and the loose debris had cascaded out, smothering him. We didn't stay until he was finally recovered, but when he was, he was dead. Sid Hichisson had the unpleasant task of trying to revive him, but he had been asphyxiated.

About this time I was put on a re-rip at the entrance of L16 main gate with another re-entrant by the name of Don Waterworth. Also working with us was Bill Bimson or "air electric" as he was known. He got this name because, if ever an operator was required for a haulage engine, Bill would say "I'll do it, I've papers for any thing, air or electric" We were replacing damaged arches there, which had been crushed due to ground movement, as they were near to an air-crossing.

I stayed with this job for about 4weeks, after which I was transferred to the top of E3 where an engine house was being constructed to house the manriding engine that was going to replace the terrible monorail. I was working with two Poles, Joe Domanski, and Zygmunt Misczuk. These were two who had previously worked at Stones when I was there. On the opposite shift to us were Alan Davies (overtime king), Don Roome and Jack Hamer. On this job I worked all afternoon shift, because I could get 2 hours overtime in every day and a shift at weekend as well.

There's a story worth telling about Alan Davies, "The overtime king". Underground, we had warning notices and others giving advice and instructions. One of these notices was in the sub-station, and it was giving advice about the treatment of electric shock. It showed the figure of a man lying prostrate, being given the"Kiss of Life", and some wag had drawn a balloon at the side of the man's mouth who was doing the resuscitation, and in it were the words, "It's Alan Davies, they've stopped his overtime!!"

Just at that time I lived for overtime, I was drawing twice the money that I had been on at Sellars Ltd. When we did 2 hours at night we got a food allowance. I usually took mine in chocolate biscuits, which I brought home for Jeff to eat! We were using a "Mindev" loader (a small edition of an Eimco) with which we filled out the dirt on to the belt on 3/21 level. We set big two-piece German arches in the drivage, which was about 15ft high and 17ft wide, and when completed, the engine house was about 30yds long. After finishing this job, we carried on sorting the cross level out. The floor needed levelling, rails laying, and crossings put in, and I worked on this job until August 1975. One Friday afternoon shift, I was put with a gang in a drivage, just for the day. While I was with them I managed to break a bone in my left hand. It was done so simply, there was a guard rail on the Eimco 622 on which I rested my hand, and, as I was passing covering boards up to the man who was covering the arch crown in, one board slipped out of his hand and struck me. I didn't realise that I had broken it, and I worked on the Saturday and the Sunday. My hand swelled up, and when I saw the sister on Monday afternoon before I started work, she told me to go to the infirmary for treatment.

I finished up in plaster, up to my elbow, and that, more or less put paid to my working with Ziggy and Joe. I didn't want to go off work, so I asked to be put on the surface until the plaster was off. I was relocated to the baths, assisting the superintendent, Harry, who had been underground and had been invalidated out at some time.

While I was with him, we re-organized the shower system in the workmen's baths. There were a lot of shower heads missing, and a lot of the valves were leaking. Harry went down into N Wales to Bersham Colliery, which was closing down, and salvaged a load of fittings for us to re-furbish with. We sorted out quite a lot of the problems while I was with him.

Just before I was due to go back underground, I had a word with John Connaughton, the undermanager of our section, and I asked him about getting back to the job of deputy again, and he promised to see what could be done about it. He was as good as his word, and when I went back down pit, I started with Brian Waring to do my 5 days supervision in the stable-end of L16 main gate.

I had never fired coal in the solid before, at least not legitimately, as it always had to be pre-cut when I was at Stones . New types of explosive had been evolved to meet these requirements. The one that we were using in the stable ends at Parkside was called Unigel. We also had a new type of stemming, which was a water-based gel in a plastic sleeve that had to be slit with a knife before use.

To fire, we used a 12 shot exploder, which contained a re-chargeable battery, and this exploder was returned to the surface every weekend for re-charging. When the circuit was complete, before firing, a red light would appear as a test for the circuit. To fire, a button was depressed to dis-engage the test circuit, the firing key turned, and the round fired. The dets used were milli-second delays, and the bang sounded like one explosion, when in fact there were usually 6 separate bangs. These explosives and detonators were used like this to avoid any chance of a gas ignition during firing. The idea behind this train of thought was that there was sufficient time lag between each explosion to fragment the coal, but not enough time for any gas to seep out during the firing of the round.

The worst job was to get the powder to the face, which came underground in 5lb pouches, made from scrap conveyor belt. When I was a deputy at Stones, the price to carry a pouch of powder was 1/6d or 7.5p in decimal. At that time in 1959 it wasn't a bad price, but the price had never been reviewed, and was still only 7.5p. No one wanted to carry it, and we had to beg and cajole men to carry it in. The men who did carry it would empty the powder sticks into a hessian sandbag, tie it up, and throw it on the bottom belt as they walked inbye. The bag would fall off at each return-end plough and would be thrown on the next belt again as the men reached it. Of course, accidents happened, and sometimes the powder would fall off before it reached its destination. When this occurred, it was left to the deputy to go and find it. If any powder sticks had split open in the bag, you could look forward to a bad head from the nitroglycerin, if it got on your hands.

Continued...