Parkside Memories, 1959 to 1989

Starting to Cut the Run Rounds

Work was started in No2 shaft. First of all, the obsolete shaft pipes, ventilation pipes, concrete pipes etc were removed. As I said before, there was a connecting tunnel at the bottom of the shaft to provide access and to create an airflow system. The 3 deck sinking platform was taken out and dismantled and the guide ropes lowered to the bottom and anchored to a receiving frame known euphemistically as "the hovercraft."

Next, a platform was constructed at the horizon to be worked. This was anchored securely to the sides of the shaft, and it was made from RSJs and chequer plate, strong enough to bear the weight of an Eimco 622 loader. A trapdoor lifted by means of a crab winch attached to the shaft wall gave access to the sump, and when this was required, the winder would hold one hoppit at the pit bank, unlatch the split winding drum and slowly lower the other hoppit at 4ft per second down to the "hovercraft."

In the tunnel at the shaft bottom, a framework carried six 30ins electric fans and four 24ins compressed air fans. The electric fans were running all the time and the c.a. fans were there as a standby. The frame itself acted as an airlock and two steel doors gave access through the frame. As the Coal Mines Act required all fans at that time to be monitored 24 hours a day, three deputies were assigned to the job. Unfortunately I was one of them. The other two were Ronnie Adamson and Frank Atherton. What a soul-destroying job it was! I hated every minute of it.

Both Frank and I tried to get transferred to other collieries, but without success. It was a system of loose and tie, which meant that you couldn't go home until relieved. If your mate didn't turn up, you stayed for half a shift until the other man could be sent for. I thought that I was safe from being sent for, as I lived 8 miles from the pit, but one night, about 2 30 am, we were awakened by a knocking on the door. When I looked out of the window, a Coal Board wagon was standing there. I went down and was told that Ronnie hadn't turned in and that Frank was still underground. I threw the bike onto the lorry and off we went.

You worked 40 minutes longer than the other deputies as it took 20mins for the hoppit to get down and another 20mins to go back. Also, if mucking operations were in progress, you waited until it was complete before they would open the doors and send the hoppit through.

The noise from the fans was incessant and when you finally came to the surface your ears were singing, as no earmuffs were issued those days. Today, HSE would have had a field day with them. At first when we started to attend the fans, we stayed in the airlock to keep out of the noise, but later on a small cabin was made in the joiners shop, and we took this down in sections, put it together, and at least had some respite from the din.

We had a library of books to read and I made a seat from a piece of conveyor belt that would double as a bed as the night shift was usually spent asleep. In fact, when I came down to relieve Ronnie off the night shift he would be still asleep with his feet ledged on the door, and as I opened it, they would fall with a bump, waking him up!

We were down there about six months altogether, by which time No1 run round had been constructed and part of No2. The main surface fans had been installed and the sump tunnel reverted back to being a pumping station, accessed from No 1 shaft via a series of ladders from No 4 horizon.

I began shotfiring operations about half way through the excavations of No2 run round. Stones colliery had ceased production completely about midway in 1960, when the Plodder or Ravine seam proved too dirty to mine profitably, and the rest of the men and officials were dispersed to various other collieries. Albert Johnson, Alf Rigby, Tommy Wynne and Tommy Walker were sent to Parkside. We got an influx of men from Landgate with Pat Scully, Trevor Jones and Colin Perks. A lot of the original deputies who were there in the sinking had been either promoted to overmen, or had left.

It was about this time that I got my first car, a Standard Vanguard beetle back, reg. no. KLR 471. I had been taking lessons with our Bill and also with Wigan Motor School. Finally I passed out as a driver and bought this 1949 car from Ernie Wilkes, for the magnificent sum of £90.

My Standard Vanguard car.

Dad and our Bill my came up to the pit one night with it and I slung the bike into the boot, never to be used again. It was hard graft going to Parkside on a bike!! Later on I used to give the lads a lift home in the car. The boot lid would never fasten down and I recall Pat Scully saying that it sounded like I had a "Ventilation Tube" in the boot. It was round about this time that the M6 was being driven through Ashton and Wigan, and soon it was possible to get on it at Goose Green and by-pass Ashton. There was a car full for most of the time, and they all contributed 2/6d(12.5p) week towards the petrol. As the buses ran only every hour, it was a lot more convenient by car.

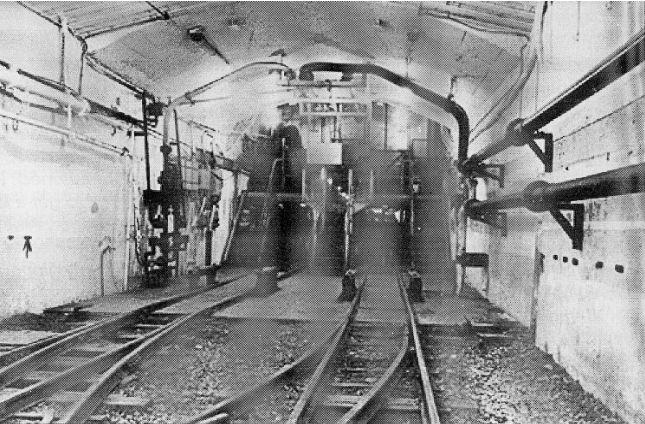

When work started on the run rounds, the hoppits were still used for mucking out, but they were cut down in height to about 4ft. This allowed the Eimco to tip its load into the hoppit otherwise, the dirt disposal system was the same as when the shaft was being sunk. The No2 shaft area was excavated to the North for 25yds at around 20ft in height and 26ft in width. This area being supported by cambered girders slung down from the surface.

The method of excavation was as follows: - Long narrow headings were driven on either side of the roadway so that the concrete walls could be made, these being tied into the original shaft walls. The headings were driven 6ft wide, and, when complete, acrow shutters were placed in position to form the wall and braced off the sides with scaffolding poles. The concrete was sent down the shaft ready mixed in the pipe that was previously used during the sinking. It was directed, first into a "placer" which in turn delivered it into the shutter, vibrating pokers being used to remove any bubbles.

Once the concrete was being poured, it was kept up in a continuous stream until the wall was complete. The walls were 2ft 6ins thick, and it took around 16 hours for the concrete to "go off" when the shutter could be stripped, and got ready for the next operation. As concrete sets en masse it generates quite a bit of heat, and as the shutters were removed, steam would be seen rising from the wall. When shot firing was taking place, the men had to be withdrawn to the surface. To fire the shots, the original shaft cable was used, this having been installed when parallel mains firing was used in the shaft. A word of explanation on this: when the shaft was going down, difficulties were experienced. Conventional methods of operation weren't working and there were a lot of miss-fires, so the parallel mains system was adopted.

The primer cartridges containing the detonators were assembled at the magazine and coupled in parallel to a bus bar, the whole assembly being taken underground in a special box, lined with felt. When charging had been completed, the bus bar was connected by means of two pins to a cable, suspended from the surface. The firing operation was carried out from a small cabin at the side of the shaft, where the cable pommel was inserted into the socket, after a test had been carried out on the firing circuit, using a "Megger". A special key was inserted, first of all into the alarm klaxon, which sounded while the shots were being fired, and then into the firing slot, turned, and held there whilst all the round of shots were fired.

The explosive used in the shaft had been Polar Ammon, which was a type of gelignite. This, of course, wasn't permitted in tunnelling and we reverted to conventional explosive, Polar Ajax, with half-second delay detonators. Although we used the shaft cable, an Schaffler 100 shot exploder was used for detonation.

When both of the walls had been excavated and concreted, the middle section known as the "dumpling" was removed, the roof being supported by roof bolts and plates, until sufficient ground had been exposed to allow the permanent supports to be set. To place the cambered girders in position, holes were drilled in the roof and bolts with eyelets anchored in them. To these, pulleys were attached, and a wire rope passed over them, one end of this being attached to the end of the girder and the other end snagged to the Eimco bucket, thus the end of the girder could be pulled up to the top of the wall.

Once there, it was secured with a chain and the performance repeated with the other end. About six girders were placed in position like this, with the curve on the camber facing downwards, and then the anchor bolt and the pulley were re located at the centre of the roof and each girder turned over so that the camber was at the top. The girders were located to their final position by using pinch bars to move them along the wall. Concrete slabs were placed inside the web of the girders as cover and, using chock-pieces, the girders were blocked securely to the roof to complete the job.

As the excavation moved forward, the hoppits were placed on specially constructed trams, and pushed manually inbye to be filled. There were about 20 cambers set at yard intervals, and then a head wall was cast. From here a short tunnel of 11x12x9 arches was driven 20yds and this housed the air doors when the run round was complete. As the job moved forward, the tram and hoppit were moved back and forth by means of a 620 Eimco without a bucket, used as a loco, this was a loader that ran on rails as opposed to the 622 which was tracked and pre-fabricated sections of track were laid for this purpose.

The next stage involved the construction of a half arch junction, to enable both curved roadways, which formed the access to No1 shaft to be constructed simultaneously. At this point a panzer conveyor was installed in the completed roadway from the junction, to No2 shaft, where it was ramped up to deliver into the hoppit. To feed the conveyor as the headings advanced, a small train of side-tip trucks was brought in, the Eimco 620 still being used as a loco. Using pre-cut and numbered pieces of wood slab as covering in the web of the arches, thus ensuring that both arms of the run round were symmetrical, formed the curves in the roadway. At either end of the two arms, when the point was reached, a compound junction was constructed of girders to enable excavation of the pit bottom area of No1 shaft to be carried out.

At this point also, head walls were made where the main North and South tunnels would be driven. To excavate the pit bottom area to No1 shaft, the same pattern of work was carried out as had been done at No2 shaft, namely concrete walls and cambered girders.

As we were constructing No2 horizon pit bottom an incident occurred, and the remaining cambered girders had to be modified. We were approaching No1 shaft from the North side, the walls had been poured, most of the cambers set, and the workmen had chocked the top of them to support the roof. The entire roof was roofbolted and we had about 5yds of ground to take out to complete the job. There was a bit of movement in the remaining strata to be excavated but nothing to give us concern.

I was shot firing at the time and had just charged a hole in a large piece of loose rock that was hindering progress. I cleared the area, ready for firing, when, suddenly there was a roaring sound and the roof above the cambers caved in, bringing all the steelwork with it! The cambers which were in three pieces, with fishplated joints were torn apart at the joints, and there was a massive cavity where the roof had caved in about 12ft above the line of the cambers. My main problem was that the shot was still charged and buried under tons of debris. It was retrieved 24hrs later. If I had managed to fire the shot, I would no doubt have been blamed for causing the catastrophe.

All the damaged steelwork had to be taken to the surface and repaired. This time, the cambers were plated and welded, as were all subsequent cambers used. It took a good three shifts to fill out all the debris and when the cambers were back in place, the cavity was filled with concrete, which took 72hrs to pour, and cost £15000. It was later found that bed separation had taken place above the plane where the roofbolts had been inserted. I got a rocket from the manager because I had split a packet of powder to make up the charge, and he said that he wanted to see the charge when it was recovered. I don't know whether he saw it or not, as it was recovered on another shift, all I know about it was that I never saw it again!

At the time that excavations were taking place in the run rounds, No1 shaft was being commissioned and equipped by a firm from London called Telemeters, who were responsible for all the electro-pneumatics, with Westinghouse Ltd fitting the ram gear and platforms etc. In multi-rope koepe systems both cages work independent of each other and there is a counter weight to each cage, rather like a lift system. At each inset a "pocket" was made to accommodate the gear for decking and loading. The platforms had rams to lower them into position, but to raise them; they were assisted by counter balance weights. The pocket was about 6ft deep and extended back into the inset for 10yds, covered with a false floor of chequer plate, complete with an inspection hatch, and there was a similar arrangement at Nos 2&3 insets.

At the No 4 level there were just 4 arches set to make a refuge hole. From here a system of ladders was the only access to the sump. It was 185ft from No 4 to the bottom of the shaft, and there were platforms at intervals between the ladders. I think that there were 5 short ladders and 2 long ones, these having safety cages round them. In this maze of steelwork were housed the guide rod weights and the override guides for the cage. There were 12 guide rods altogether and each guide rod had 16 tons suspended from it in the form of cheese weights.

The men in charge of excavations in the run rounds were Alec Fraser and Charlie Duffy who worked shifts of 12hrs each. They were Scots from Glasgow, staff men for Kinnear's, and they had accents that you could cut with a knife! When Charlie was putting a line on for the tunnellers he would stand behind the strings, looking at the lamp at the tunnel face and give the following instructions. "Tae ye, tae ye !" or "Frae ye frae ye !"{To you or away from you}. He was a great character though. He suffered a lot from pains in his joints, brought about, so I was told, from "bends" due to working in compressed air tunnels under the sea. Kinnear's were specialists in sewage tunnels and associated works, so it was a new venture to work in deep mines. They still had the contract to equip No 2 shaft after they had completed the run round, and also the construction of the tippler station, but the spine tunnel contract was awarded to George Wimpey and Co Ltd. I was told by the men from Kinnears of what it was like to be working under pressure in a tunnel. 4 hours were spent going into compression, 4 hours working, and 4 coming out of compression. Occasionally, when the men wanted to go out on the ale, they would try to shortcut the system and go out via the airlock where the spoil went. This might work, but sometimes they were afflicted by the "bends" when nitrogen bubbles in the bloodstream got into their joints. When this occurred, they had to be placed in a decompression chamber to sort them out.

Continued...