Parkside Memories, 1959 to 1989

Parkside Memories (1959-63)

"I need three volunteers for Parkside." We were all gathered in the report room at Park Collieries (Stones) in Liverpool Rd. Ashton in Makerfield in September 1959, the Orrell Yard seam had just been exhausted, in fact, in the area of Seneley Green, we were only a few yards from the surface.

John Bradshaw, the manager at Park Collieries had called a meeting of all officials, deputies and shotfirers, to ascertain where everyone was to be deployed. We had quite a few choices, because at that time Golborne, Sutton Manor, Clockface, Woodpit and Lyme pit were all in production.

The manager continued, "It's a new pit, and you will see things there that you will not see again in this area." I thought for a moment, and my hand went up. "I'll go," I said. Frank Bourhill and Ronnie Adamson also volunteered, and so my fate was sealed for the next four years or so.

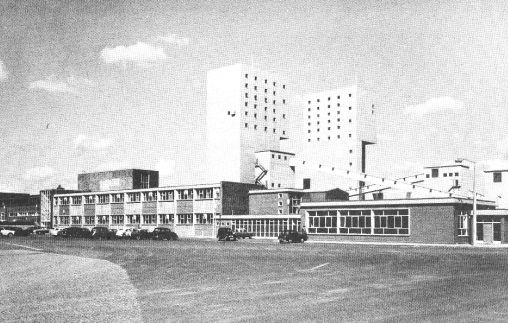

The three of us arranged to meet in Ashton to go to the pit for a look round, so we caught the 10.00am Warrington bus on the Saturday morning after working our last shift on the Friday, and made our way to the pit. Until then I had never been past the new colliery site and, as we approached, we could see the winding towers in the distance, looking for the entire world like two tower blocks of flats. It was quite a distance from the main road and walking along the access road with mixed feelings, we had no idea of what lay ahead. It was about 500yds of a walk to the main office block, and we passed a weighbridge on the left hand side of the access road, just past the bridge, under which ran the lane to the farm.

Parkside after surface buildings completion.

The first phase of the new buildings was complete and we went in at the front entrance to speak to the receptionist, Maureen Broster, who pointed us in right direction. "Go up the stairs, along the corridor and you'll find the deputies room". We finally found the right place and, going in, we met up with a couple of men dressed in shaft boots and yellow waterproof bib and brace overalls. These turned out to be Sam Johnson and Tommy Fildes, having a brew and a bite to eat. Introducing ourselves, we chatted with them before our meeting with Joe Corday who was Safety officer/Training officer etc. and he explained to us the position. There was a full complement of officials in the shafts at that time, and for the time being at any rate, we would be employed on the surface, paid deputy's rate, but working as labourers, doing any work that was required of us. We came away, after making arrangements to start the following Monday morning.

Monday morning came and I rode off on my bike. Going to Stones colliery hadn't been too bad, as it was only about four miles, but Parkside was a different thing altogether, because it was eight miles and it seemed forever. Those days I couldn't drive and didn't have a car, but I got there eventually. We were given lockers in the only baths available at that the time, situated in the main block and later to become the Junior Management baths. The General Manager had his own bathing suite situated near his office and only used by him and any visiting "top brass".

It seemed strange at first to be wearing wellies and a flat cap instead of pit boots and helmet, eating canteen food instead of "tommy tin" sandwiches. We were shown around the site. (It was called a "site", never a pit or a colliery, for a long time.) What a strange place it seemed, nothing like the pit that we had been used to. The sinking winders with their masses of ropes going through holes that had been left in the tower walls and seeing the condensation rise as the shaft doors were opened to allow the hoppit to pass through on its way up and down the shaft. It was a strange sight seeing these massive buckets coming up full of spoil, and hearing the air whistle as the winder was signalled to tip. The South African shaft bosses were still in charge of operations at that time with names like Schutte, Van Dyke, Kalitz, and Steinkampf. Tales were told of their legendary drinking exploits, car wrecking etc. At that time deputies wages were around £19.00 per week, with the South Africans on £65.00 per week, and as they were in a foreign country, they didn't pay income tax. When they rode the shaft, they came up on top of a full hoppit, standing on the spoil, and, as the winder slowed down at ground level, strode across the open shaft, onto the top of the shaft doors and dropped off. They wouldn't waste a ride, as time was money!

The shaft workers were in gangs of ten, each with a shift boss. The shift lasted eight hours and each shift overlapped with the next so that the work was continuous. All the sinkers wore yellow oilskins consisting of bib and brace trousers, jacket, wellingtons and a sinker's helmet with a large brim at the back to spill the water. They wore pieces of towel or rags round the neck to absorb any water that missed the helmet. The chargehand wore shaft boots instead of wellingtons and these, made by Dunlop had rubber tops and leather sole, furnished with steel caulks and an instep plate. Most of the deputies working with the shaft teams had managed to acquire a pair, no doubt for "services rendered".

As each team mustered ready for work, they climbed into the hoppit standing on the shaft doors. The banksman signalled the winder to lift the hoppit up slowly until it was clear of the doors, which were then opened and the hoppit lowered slowly to below the shaft top. The doors were closed before sending the hoppit away at speed, and these doors were always kept closed when men were in the shaft to avoid any debris falling down. A small stone falling 2000ft could cause a serious injury. I recall one incident when we were stripping the ventilation tubes after the main fan was installed. The men were using jiggers to cut through the bolts, when a piece of rust fell from the side of the tube and cut a man's hand so badly that it needed 10 stitches.

When we arrived at Parkside the shafts had reached bottom at 2656ft. Nos. 2&3 insets had been excavated, and No1 inset was being constructed. To make the insets after the shaft was sunk took some ingenuity. The insets hadn't been made as the shaft was being sunk because they were after a record for shaft sinking. They apparently achieved this with a distance of something like 163yds in a month. To make the insets later, the following had to be done.

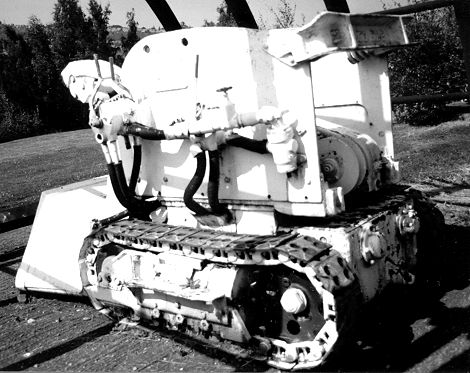

First of all, pockets were cut into the side of the shaft wall to accommodate two RSJs.which were 30ins deep in the web. When these were positioned, 10x8 cross girders were laid across them and secured. These in turn were covered with railway sleepers, and finally corrugated sheet nailed down over the lot. Thus a false bottom was made enabling the mucking out to be done using Eimco 6/22's. (Compressed air driven loaders on caterpillar tracks.)

An EIMCO 6/22.

(Photo taken at Wakefield Mining Museum).

The sinking platform was positioned 30ft above the inset being constructed. A breather pipe was inserted through the false bottom to enable any accumulated gas to escape to atmosphere, because, as the shaft wall had not been completely sealed, where the coal seams were encountered gas escaped in great quantities, sounding just like jets of compressed air.

One day, after we had been at Parkside a couple of weeks, Joe Corday said to us "I'm going to take you all down pit to see how the No.1 inset is being made". We got kitted out in waterproofs and made our way to No.1 shaft. Until then we had never been underground at Parkside. We clambered into the big hoppit which I remember very well as I sprained my big toe putting my foot in the toe-hole on the side of the hoppit. It was partially blocked with dirt and my foot slipped.

It was a smooth ride, surprisingly, as we had been only used to cage riding before this. The shaft appeared huge as it was devoid of any gear, except for service pipes delivering water, compressed air and concrete. 26ft in diameter, it was a lot bigger than the one at Stones', which was only 15ft across. We couldn't see the bottom as there was always a mist hanging in the shaft, due to hot air rising up to meet the cold air dropping down.

As we finally approached the stage, we were struck by the amount of illumination present. Under the stage, a big cluster of lamps made the working area very bright. The men working in the sump didn't need their cap lamps, and these were hung from the guardrails on the stage, to be picked at the end of the shift. Because the Coal Mines Act covered the operations, cap lamps had to be issued, even though they were never used. It seemed a bit silly to me to issue them.

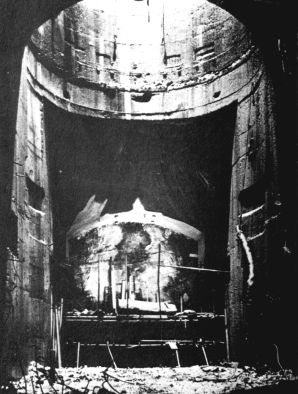

(This is a picture taken from Don Anderson's book, "Coal" showing the work being carried out on an inset, possibly either No2 or No3)

The light shining down the shaft is from the cluster of lights under the sinking stage, which is suspended above the roof of the inset.

Another thing that amazed us was the seeming lack of support. We had come from a mine where props and bars were used and here it appeared the roof was self-supporting. It was actually supported by a system of roof bolts, a something that we had never seen before. We stayed a while watching operations. An Irishman, sat on a concrete wall shouted down to us "Hey deputy, give us up the banjo" We were non-plussed at this request, until Joe said; "He wants the spade". This was our first encounter of "Paddy Speak".

It wasn't long after this that the job was completed at No.1 inset and we got the job of moving the big girders that had been used for the false floor. These were loaded by crane onto a low loader, hauled by one of the NCB lorries on the site. I forget the driver's name but when he tried to make the run up the slope towards the magazine, where the girders were being dumped, the weight on the low loader was too much for him and his wheels started to spin. We had to put one of the girders on to the wagon to give him some grip!!

As this inset was being completed, there was one incident worth recording. The pipe, placed in position to allow any surplus gas that built up under the false bottom to escape, got blocked somehow and gas built up under the platform. We were told what had happened by one of the deputies. There was a gang of men working at the inset, the floor started to tremble violently due to the gas pressure, and there was a mad scramble for the hoppit. One of the men, an Italian chargehand named Giovanni Bersani, never went underground again and ended up selling ice cream in Newton-le-Willows!

The deputies at that time were as follows: - No1 Shaft, Harold Craggs, Jack Clayton, Harry Meagher. No 2 Shaft: - Jack Mawdesley, Wally Thomas, Tommy Fildes.

Extra to these were Sammy Johnson and three management trainees, David Bentham, Brian Dunleavy and Selwyn Carter. Harold Craggs and Jack Clayton immigrated to Australia and so did David Bentham, who started his own tunnelling company out there. Brian Dunleavy and Tommy Fildes left to work in the S.Wales coalfield for the German firm Thyssen. Jack Clayton's nickname was "Wa'bowts" a name given to him by the sinkers. The South Africans were used to sinking through hard rock, and as such had never encountered coal measures. When they came across these at Parkside, they were told to secure the sides with rock bolts and mesh to stop any debris falling on them. They didn't like this extra chore, even if it saved accidents from occurring. Jack Clayton was very conscientious about this instruction, hence his nickname.

We were told of another man who had been at Parkside just before we arrived there. He was Jack Smith and he had been employed as a safety officer before Joe Corday. He wasn't well liked, especially by the contractors, who didn't like being restricted by a lot of petty regulations. Jack had apparently got up someone's nose, because this particular day, he had gone across to the pit to go down, climbed into the hoppit, clad as usual in his rubber suit, white towel around his neck, and been knocked away. As the hoppit got below the shaft doors, the banksman, who was in fact, the aggrieved person, knocked "hold", shut the doors, and carefully poured a 5 gallon can of black rope oil down the shaft on to the hapless Jack, who, although mouthing curses, was in no position to do anything except stand there and take it. When the deed was done, the banksman knocked the hoppit away again and packed the job in. (You didn't need to serve notice when you worked for contractors).

Jack came straight back up again, breathing fire, and went off to see the General Manager, Albert Taylor, who promptly kicked him out of his office for spilling oil on the floor!!

The main company in charge of operations at Parkside was a South African firm, Roberts Construction Co, of Johannesburg, which in turn sub-contracted a lot of the work to a Scottish firm of specialists in shaft work, Kinnear Moodie & Co. Ltd. I remember seeing some pictures on the wall of their office, showing shots of some of jobs that they had been engaged in. A lot of their work was carried out in pressure chambers in undersea work, such as constructing sewage outfalls, so really, Parkside had been their first taste of real pit work.

The work progressed on a seven day, three shift system. Days, nights and afternoons. On the change round from nights to afternoons, a lot of the men didn't go home, but bunked down in their cabins, or even slept in the pile of ventilation tubes which were stacked in the compound. I had a look through these cabins one day, and they were in a filthy state, but the bosses' cabins were as different again. The two Master Sinkers were Ken Scott, a Rhodesian, and McAlpine, a South African, and these two were in sole charge of the shafts.

Looking after the interests of the NCB was the Agent Manager, A.E.Taylor, and a strict disciplinarian of a man, who had been sent to Parkside from one of the collieries in the St.Helens area, I believe that it was Lea Green. The men knew him as "Owd Albert." I recall Jack Moorfield, who came from Mains Colliery, saying that he had worked with Albert Taylor in his youth, and when starting at Parkside had greeted Albert with familiarity, saying to him, "Art'awreet Albert?" To which Albert replied "there's a lot of watter gone undert'bridge sin we worked t'gether Jack." Jack said, "Aye, ah know what tha meuns" Knowing that Albert was now Mr. Taylor.

When the "mucking out" was being done, all the spoil was taken from the shaft in Muir-Hill 3ton dump trucks, and spread in a hollow towards Newton station, and it was on this ground that the permanent rail track was laid later on. The dumper drivers had to drive their trucks without cabs, exposed to the elements. This was in case the truck went over the edge of the tip, and it would then allow the driver to jump clear, and save himself.

Continued...