Childhood Memories

Comic Paper Recollections

During the war, it was still possible to get comic papers, even though they had shrunk in size. The Dandy and Beano were the main ones, but as we grew older, the ones we read were such as Wizard, Rover, Hotspur and Adventure. The Dandy and Beano had characters like Our Gang, a cartoon version of the Hal Roach comedies of the same name. I can see some of the characters now, Scotty Becket, Alfalfa Switzer, Rosie, etc. Also in the Dandy was the legendary "Desperate Dan" who lived with his Aunt Aggie and ate cow pies complete with horns sticking from the crust, Keyhole Kate, the nosy girl who enjoyed peeping through keyholes. Doubting Thomas, who had a curl on top of his head in the shape of a question mark, and whose catch phrase, when asked to do something was "I doubt it but I'll try." The front of the Dandy was covered with the adventures of Korky the Kat, whilst the Beano had an ostrich named Big Eggo. The Beano had Lord Snooty and his Pals, Big Fat Joe, Snitch and Snatch, the twins.

There was another character introduced into the Beano during the war and this was a caricature of Benito Mussolini, the Italian dictator. Musso da Wop, he's a big a da flop. He was always portrayed as doing really stupid things I recall one such incident that "Musso" did. He was playing with the other children and he built a snowman on top of the cellar grating of a bakery shop, and as the hot air rose, the snowman melted!

We looked forward to these week in and week out. The Dandy and The Wizard were delivered with the daily paper "The Daily Dispatch" but all the others were read by means of swapping amongst the other children in the neighbourhood. Gordon Ackers was one who would swap with me on a regular basis and we would sit in the vestibule in the dark, swapping comics. The Wizard had stories of schooldays like "Smith of the Lower Third" The story of a boy from the slums of a Northern town, who gained a scholarship to a public school, and we waited for each episode agog with excitement, as Smith outwitted the "toffs". I think that we related to Smith as he was always portrayed as the underdog it also had stories of great adventure like "the Wolf of Kabul", where an Englishman, disguised as an Afghan, had all kinds of hair-raising adventures with his companion Chung, who was of Mongolian descent, with Asiatic features and built like a bus. The Wolf had twin daggers that he kept sheathed at his waist, and Chung was armed with an ancient cricket bat, bound with brass wire. He called this "clicky ba'" and he used it with some force on the ungodly. Stirring stuff indeed!! It was in the Wizard that we first encountered the legendary Wilson. He was an athlete of some 140 years of age, who had as a young man, gone to the Himalayas, and there met up with a mystic who gave him a drug which slowed his heart down to some 4 beats per minute, thus enabling him to run at a fantastic speed, annihilating all the opposition. He was the only man to run up Everest without oxygen and barefoot, clad only in an old fashioned woollen running suit!! We lapped it up as small boys.

The story that sticks in my mind from the Hotspur comic is the one about another public school named Red Circle. The adventures that the boys got up to were fantastic to say the least. Stuff like midnight feasts in the dorm, playing practical jokes on the Headmaster and teachers, and as we were Grammar School boys at the time, we could relate to their antics.

Dad liked to read comics as well and one day, a workmate of his gave him a pile of Wizards from prewar days. These were a lot bigger in content than the wartime editions, and as they were in sequence, he hid them from us, so that he could enjoy them himself, reading them. He only gave us the ones that he had read, until we prevailed on Ma to tell us where he kept them, and then we had them all out when he came in from work!! I don't think that he was really pleased, but he didn't say anything, at least not to Billy and me.

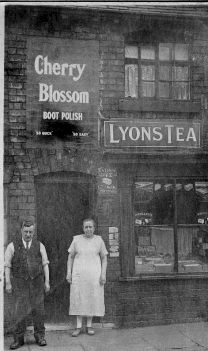

The Shop in Hallgate

About this time during the war, we only went to school for half a day, as the shelters hadn't been built and the government didn't want a lot of children there at any one time, so as to minimize the risk of casualties in case of air raid. Some of us went during the morning and the rest in the afternoon. Ma was helping Grandma Bradshaw with her pie shop in Hallgate, so I was told to get the bus and make my way to Wigan after school. The shop was situated at No 47 Hallgate in a very old piece of property. We kids thought that it was fantastic. When we went into the shop, the counter always looked high. I suppose that it was normal size but with us being small it just looked big. Grandma sold sweets, cigarettes and a bit of grocery which she bought from Holland and Clough, the wholesalers who had a place in Great Acre.

She used to make pies in the back room, meat and potato, and steak and kidney, I can see it all now, the old cast iron stove, two big pans with double handles, filled with potatoes, onions and stew beef, bubbling away, ready to be put into the pie cases. There was a baking table where Ma and Grandma kneaded and rolled out the pastry. Dad made her some cutters from tinplate and soldered handles on them so that she could cut out the bases and lids. Grandma lined the tins with pastry and then, using a big spoon, ladled mixture into the pies. Ma then lidded and crimped them, trimming the surplus off with a knife, made a hole in the top, and they were ready for the oven. The room behind the shop where the pies were made was only small and the ceiling had been removed to allow the steam to escape. We kids used to go up the narrow winding stairway and lie there looking down on the work being done. Ma, seeing us would say "Mind what you are doing up there and don't fall down." Grandma used the front room upstairs as a store room for the shop supplies, and I remember seeing bundles of bags and paper up there. Just inside the stairwell was the bin where the flour was kept and this had a hinged lid and a scoop to get the flour out with. Grandma had a regular clientele for the pies and it was Granddad's job to go out at dinnertime with the pies in a big square basket, covered with a chequered cloth. He took a jug of gravy with him and sometimes slices of bread and butter. I think that Grandma must have had some of the first sliced bread in Wigan. It came from Rathbones and was held together by an elastic band, not wrapped in any way.

Granddad went down to Santus's and also Coops and the hosiery factory in Dorning St, taking his pie orders at dinnertime. He had worked in the mines but he had nystagmus, which is a disease that affects your eyes, due to working in poor light, and he had had to leave. Grandma opened the shop as a livelihood for them both, and not being aware of it at the time, had employed Granddad instead of him employing her. This fact cost them their old age pension at 65 and they both had to work until they had reached the age of seventy.

The shop was closed down about 1943 because Grandma didn't want the hassle of ration books and coupons, and by then they had both reached the age of 70 when they could draw the old age pension, a princely sum of 10 shillings a week (50p) She only lived for another two years before dying from cancer.

Next door to Grandma's shop was a boot and shoe repairers, run by a crippled man, Peter Collier. Boot and shoe repairing seemed to be a trade that crippled people were put to, probably from the fact that the job could be done sitting down. We kids were fascinated to watch him work. He had one of those spindles that are common in all boot repairers, with the polishers and buffers on.

By the side of the shop there was a narrow entry, which was kept, locked with a brass Yale lock and key, and in this passage were two toilets, one for each shop, and each toilet had a lock on the door. We thought this was great when we could go to the toilet and lock ourselves in! There must have been another building attached to the wall of the shops, because on the passage wall were stuck pieces of plaster and horsehair which we pulled off to use as chalk.

Next door to the entry was a clothing factory, "Standwear Manufacturing Co". It was a sewing factory that made shirts and they had a folding gate that was put across the doorway when they locked up at night. We children used to play in this doorway, pretending that we were in a lift, and sliding the gate back and forth.

As I spent quite a lot of time in Hallgate, I got to know some of the children who lived there quite well. Two of my playmates were Jimmy Horsfall and Norman Green. Norman's Grandma was Mrs Havard, who along with her husband had a fruit stall on Wigan market. Where the sorting office stands today, there was a big pond called an EWS (emergency water supply). It had been put there in case of fire through enemy action, but it drew all the children like a magnet, as water usually does.

We all gathered there during the school holidays to sail boats or just throw stones into the water. Hallgate those days was quite a thriving community, with lots of shops and people living in the houses there. In "Little Hallgate" i.e. the part from the Crofters down to the pub on the corner, there were a lot of shops, such as The Olde Englishe Cheese Shoppe, Clarke's fish shop higher up where the window could open on to the street, Florrie Jackson's newsagents, Swifts chip shop with its coal fired range, Mayalls paint and wallpaper, and many others.

We watched the draymen come up in their horse drawn dray, wearing aprons made from sacking, delivering barrels of beer to the Bay Horse pub on the corner, watching them drop the barrel on to a thick mat and then with a rope round either end, and through an iron ring set in the pavement, lower it down into the cellar on a sort of ramp that they carried for the purpose. All cellars those days had the same sort of smell about them, damp and musty and smelling of stale beer.

One day, as I was going to Grandma's shop I had a very lucky escape. It was when the school was only open for half a day and I had finished at dinnertime. I got off the bus at the L&Y station and made my 'way towards the churchyard as I always did. I must have been daydreaming because when I reached the corner of Bishopgate and Hallgate, I ran across the road there without looking. A car was coming down Hallgate and how he avoided me I will never know. In those days the car door handles stuck out more than they do today and, as I was wearing gloves (they were Ma's old leather ones), I put out my hand to save myself and the glove caught on the handle, tearing it off my hand. I thought my arm had been pulled off, it was tingling with shock.

The driver jumped from the car "Are you alright?" he said. I must have been as white as a sheet! When he could see that I was ok he took me up to Florrie Jackson's and bought me a book! He then took me back to Grandma's, where he told Ma all about it.

Across the road from the shop was the All Saints Tavern and here lived a Mrs Jowitt and her husband. They had a cat by the name of Toby. It was a spoiled thing and Ma was scandalized when she heard that Mrs Jowitt fed the cat on liver. She said "How can she do such a thing, doesn't she know there's a war on?"

Uncle Joe Bradshaw was a coal dealer and he delivered coal to some of the shops in Hallgate, such as Swifts chippy and The Olde Englishe Cheese Shoppe. I sometimes went with him on his rounds, we had some fun! Uncle Joe was a real character and very humourous. He had a young fellow working for him at one time called Teddy. Teddy was "a few bricks short of a load" as you might say. That of course didn't matter because you don't need brains to hump coal bags. In the wagon was an ignition switch that was "live" In fact, if you touched it when the engine was running you got a shock. Uncle Joe sat me between himself and Teddy and, touching the switch, held my hand, I then held Teddy's hand and Teddy touched the door, at which he got a shock and shouted "Aoww" I used to think it was hilarious. I don't know what Teddy's thoughts were!

One time when Uncle Joe was delivering in Longford, Warrington he was having problems with boys grabbing the tailboard and swinging on it. He said to Teddy "Ride on the back of the lorry and if anyone swings on the tailboard, throw a lump at them," Teddy lobbed a lump of coal at one and split his head for him, Uncle Joe had to beat a hasty retreat!!

I had a narrow escape once in the coal lorry. I must have been around ten years old at the time, and we were delivering coal at Little Budworth in Cheshire. We only went once a month and we took 40x1cwt bags, delivering these in 4 drops to farmhouses. The coal wagon at that time was an old Ford and the handbrake was one with a stud at the top, which was depressed to lift the brake. Uncle Joe had gone to pick up his money and had left me pretending to drive the wagon. We still had 3/4 of a load on and I managed to release the brake. As we were at the top of a hill, the wagon began to roll forward, and Uncle Joe came out of the farmhouse just in time to save the situation from turning nasty. I shudder to think what the outcome could have been!!

During the war, the only things that affected us children was the fact that toffee was rationed and that we couldn't get fruit from overseas like bananas, otherwise life seemed pretty normal. Dad got the canteen women at the pit to put plenty of butter on some barmcakes and when he brought them home, Ma scraped it off again to use on some other sandwiches. I recall seeing a bunch of bananas on a stall in Wigan market. They weren't for sale, it was just that the stallowner's son was a sailor and had brought them home for her, and she was just showing people what they looked like!!

Wigan fruit market in those days was under canvas along Market St. The stallholders stood on a row of upturned orange boxes behind the displays of fruit, which was always stacked in neatly They, served from the back. "Don't touch the front love, they'll fall over" was the cry. All the rough stuff was piled up at the back and that was what you got. The stalls were lit with kerosene lamps, which gave out a yellow glow. The names of the stallholders spring to mind, Highams, Silcocks, Havards. Ma traded with Mrs Silcock, and one day she sent me for some Victoria plums to make jam. I got 4lb but on the way home I ate "one or two" on the bus, spitting the stones on the floor of the upper deck. When I got home Ma said to me "How many plums did Mrs Silcock give you?" When she weighed them I'd eaten a full pound. Ma thought that I would have "the runs" but I didn't!

Dad got extra cheese because he worked in the pit as this sort of work was classed as "essential" We swapped eggs for all sorts of things like sugar and butter. One day, Ma had a brilliant idea; we could churn our own butter. She saved the cream from the milk for a whole week and then put it in a big Horlicks jar. After the cap was screwed on, we all took it in turns to shake the jar and lo and behold, we made butter! Ma then mixed it with "Special" margarine (this was the only margarine being made during the war) to make it go further. (She used the margarine paper for baking sheets, when she made "divilsnose", a flat currant cake) She also made us some white bread. Let me explain, during the war, flour wasn't purified, and the bran etc. was left in. We didn't realize it at the time but it was healthier for everyone, therefore, when bread was baked, using whole-wheat flour it had a greyish tinge to it. She got an old silk stocking and sieved the bran out, and there was just enough to make a few barmcakes, we thought it was wonderful to eat white bread when everyone else had grey.

Meat was rationed but offal and sausages were not. The only problem with sausages was that there was so much biscuit meal in them that whatever you did with them, prick them all over, cook them slow, fry, grill or bake them, the filling came out of the skins, and all over the pan. To feed the hens, Dad got "lights" i.e. Lungs etc from Cunningham's and these were cooked in a big pan on the fire, then chopped and mixed with potato peelings and any other household waste, bound together with what bit of mash we were allowed and any bran that could be scrounged. It must have worked because the hens kept producing eggs. Sometimes fish waste was used as well.

We got marrowbones from Cunningham's, and after breaking the ends off, we broke open the shaft, extracted the marrow and rendered it down in the oven to get the dripping. This was used instead of lard, which was in short supply, to cook chips and to use for baking. Ma made all sorts of pies at weekend, custard, naturally as we had plenty of eggs! Jam lattice pie, beef pie on a flat plate, rice pie with currants in when we had any, all kinds of fruit pies like blackberry, blackcurrant, and apple. We went to Halsall's farm near Tanpits for apples and these were wrapped in newspaper to preserve them and stored them on the rack under the stairs that we slept on if there was any enemy activity.

We even used to preserve eggs. When there was a lot of eggs coming in from the pen, Dad got some "Waterglass" This was beer finings, and, mixed with water, it was put in the big brown bread mug and eggs placed in it. It set like a white jelly and thus stop any air getting to the eggs. We used the eggs when the hens started their moult and stopped laying.

During the war all sorts of things were done to eke out the rations that we had. Butter, sugar, meat, cheese, tea, all these were rationed, as well as chocolate and toffee. Everything else was in "short supply" We had to be "registered" with a shop to get our rations; I think that we were registered with the Coop or "stores" as it was known. Our meat ration was from Tom Cunningham at Union Bridge, and this was supplemented a bit by swopping eggs for any offal that was going like liver and kidneys. When you bought anything from the shop, you had to have your book marked or the appropriate coupon cut out. The ration books were made from re-processed paper, which had little squiggly marks in it. The sweet coupons were known as "points". All coupons were ABCorD each one having a different value.

Pigs could be kept but they had to be "registered", so that when they were killed, the meat could go into the food chain. Of course, if you could get a piglet and not register it could be raised and slaughtered in the shed by having its throat cut, thus giving you plenty of pork to barter with. This was done quite a lot and "home cured" bacon was readily available if you knew where to look for it.

Delph Garage was built on illicit dealings. Bill Demings, who built it, was well known as a dealer. He could get you anything, at a price, and consequently had a large amount of ready cash that he couldn't bank. He showed Ma a money belt one day and said "there's four hunderd pahnd theer" Which I reckon would have been close on £4,000 today. When he had built the garage and filling station, the Inland Revenue got him for tax evasion!!

There was a pen on some land in Bold St where pigs were kept during the war. Ted Fishwick had it originally but he had a stroke and couldn't keep it on. I used to push Ted from the chapel on a Sunday sometimes, in his wheelchair. When Ted gave up the pen, Jack Hilton took it on and kept pigs there and he got caught killing one illegally and was fined. A disgruntled customer whom Jack had disappointed was waiting for the sound of the pig being butchered and tipped off the inspector. He caught Jack red handed, literally!!

Everyone was encouraged to "Dig For Victory" and we dug over part of the pen to grow vegetables and potatoes. We bought our seeds from Bell's the seed merchant who had a shop in Market St. When you entered the shop, you were faced with loads of small drawers in a wall fitment, where the seeds were kept. Mr. Bell would weigh these out in 1oz packets and write the name of the seed on the front. The shop always had a "garden" smell about it! I recall names of potatoes that were grown like "Kerrs Pink", "Arran Banner" "King Edward" We grew marrow stemmed kale to feed to the hens to supplement their mash, and quite a few good cabbage and peas, but our attempts at growing onions and carrots met with abject failure because we got fly in them. In the pen were quite a lot of sheds for all the hens. Although when the war was on Dad limited the amount of hens that he kept. We were supposed to have a bird for each ration book, but this never applied and we had about 30 or so.

Dad hatched his own chickens from incubators, with names like "Gloucester Glevum". He set the incubators up in the long room in the house, this being before I had it for a bedroom. There were 3x100 egg incubators in the room and he got the plumber to run gas pipes to them. The incubators had heat regulators to keep the heat constant, and every night, Dad would get the eggs out and turn them all. The eggs had a pencilled cross on one end to enable him to know which way to turn. After three weeks, the chicks would hatch and we children were allowed to go and see them. After a day, the chicks were gathered up in a box and taken to the pen and placed in a "brooder", where they stayed for about a month, after which they went into "night arks" with runs attached and allowed to graze the grass on the pen. As they got older, the cockerels were segregated to be fattened up for Christmas, and the pullets put in the hen sheds.

As I remember it there was a feeding shed as you went through the pen gate, and in here was kept all the mash and a mixing trough, cod liver oil, etc. From here there was another small shed built over an old cast iron boiler where the bones and meat that came from Cunningham's was cooked up later on in the war.

The Bone Cutter Incident

Dad had obtained a bone cutter from somewhere. This consisted of a round drum with a divider down the middle and a door at the base. At the bottom of the drum was a crown wheel with slots in it to hold the cutting blades, held in position by setscrews, and as the crown wheel rotated, the blades shaved pieces from the bones placed in the drum. To keep up pressure on the bones, there was a casting, shaped to fit into both sides of the drum and held in place by a clip placed on the projecting threaded shaft that ran from the centre of the crown wheel, up through the division in the drum. When pressure needed to be applied, the clip could be held and stopped from turning. This action screwed the pusher (for want of a better word) down onto the bones and forced them on the blades.

To drive the machine, a motive source was needed and a place for it to stand. Dad had a shed with a second storey and it was always known as the "double decker" There was a set of steps that led up to the top deck. Well, this shed had 5x4 beams to support the upstairs floor so Dad devised a real "Heath Robinson" set up. He had obtained from somewhere, an AJS motorbike with a flat tank, about 1926 vintage. This he mounted, without wheels, in between uprights bolted to the roof members and to brackets set in concrete on the floor. He took the back wheel to work and got the fitters there to remove the rim and spokes, and braze a drum on to the hub. This was fitted to the bike frame, with a driving belt over it and over the driving pulley on the bone cutter, which was anchored down on a concrete plinth, and lo and behold it worked!

He had to run this contraption on paraffin as petrol was rationed, so to start it up he managed to get a bottle of petrol from Tom Rollins the coal dealer in the nearby yard. He took the carburetor top off and filled it with petrol, kick started the bike, and once going opened the valve on the tank and the paraffin took over. It made a horrible noise when running on paraffin, so to deaden the exhaust, he passed it through a 2ins pipe which went all round the outside of the shed. As the bike had a hand change clutch and lever controls for the throttle,(advance and retard,) it was simple enough to set these so that it didn't need anyone to sit on the bike. To cool the engine, he got his fitters to weld a pulley to the primary chain sprocket, and, getting a fan from a car engine he mounted this on a piece of angle iron from a bedstead, and ran it with a fan belt from the pulley. The hens loved to eat the bone meal and it made a welcome addition to their diet.

Dad also had a couple of sheds that he had built himself called "Half-monitors" these were built with a sort of split roof with windows set in to give more light in the shed. They were built from brand new timber during the period that he was a "master poultry farmer" We also had a long shed down at the bottom end of the pen and this lost its roof during a whirlwind in 1947, killing a couple of hens in the process. In the top pen, facing the railway line, was an advertising board in the shape of two men carrying a ladder, and on the ladder were the words HALL'S DISTEMPER, and underneath LUXURY COLOURS. We would climb up the back of the hoarding and swing from the ladder!

When Dad got the bone cutter, he would send me, along with our Billy to Cunningham's shop on a Saturday afternoon, taking with us the big truck that Dad had made from a box and two motor bike wheels. We would bring back any stale sausages, cow heads, and other bones that had been left over from the week's work. We had an old army cleaver with a long handle that Dad had picked up from somewhere, and with this, we split up the heads, ready for boiling in the coal boiler.

Getting some coal from Tom Rollins's wagon, we lit a fire under the boiler. Sometimes I would imagine that I was a train driver and I would stand at the shed door, with smoke billowing from the chimney, thinking that I was on the main line! We used to use paraffin to start the fire off, and this was kept in a tin with a spout. When I think back to the harebrained things that we did, I shudder. We found that if we heated the tin over the fire, the paraffin would vaporize, and then, holding a lighted match to the spout, we got a flare, which would go on as long as there was paraffin in the tin. It never occurred to us that the tin could have exploded!!

One day, when I was emptying the boiler I got a shock, a bird had fallen in and drowned, and I grabbed hold of it as I was picking the bones out, Ugh-----! I've never forgotten it. Later on, Dad obtained a small stationary petrol engine, which delivered a bit more power and was a lot quieter. It was after this was installed that he managed to lose his finger.

It happened like this, as the bone shavings dropped on to the tray, they piled up and need levelling off. Dad would do this with his hand, and one day as he was doing it, the projecting studs that held the blades in place caught hold of his coat sleeve. His index finger on his right hand passed through the cogs of the crown wheel and pinion, and was crushed severely. Ma had to get a taxi and she took him to the infirmary. We kids were dropped off at Grandma Foster's until they got back.

On their return, Dad was groggy from the anesthetic, as he had been put to sleep whilst the surgeon removed the piece of lacerated finger. As they came through Market Place, Dad was singing in the taxi, and Ma said that she felt ashamed to think that folk might imagine that Dad was drunk!! He had to wear a fingerstall for quite a while after that and the end of his finger was always cold, as the nerve had been damaged. His writing, which was never brilliant, went really bad when he lost the fingertip.

Visits to Yorkshire

Whilst I have the pen in mind there was one incident that took place there that's worth recording. It was during the war, I think, or it may have been just before it started. We never went away as a family for a holiday, because "Th'ens allus needed seein' to." We had odd days out at the seaside, Southport, New Brighton, but even these were spoiled because "th'ens" needed feeding, and we had to come home early. We were martyrs to a flock of feathered fowls, which had to be fed twice daily, come what may. I can see Dad now, "Ah'm just gooin' feedin'" he would say, as he set off from the house with a couple of buckets of boiled up offal or potatoes and hot water. When he was working, Ma fed the grain, which had to be mixed in the correct proportion, in the morning, and he gave them the mash. He poured the hot water into the mixing trough and added the old bread and potato peelings, together with all the other stuff like "thirds", bran, layers mash, cod liver oil. He always used to mix by hand as he said that this was the best way. Personally, I couldn't see the point of it all. If ever a flock of hens were a liability, ours were. They never paid; we always owed more for the food than what we got for the eggs.

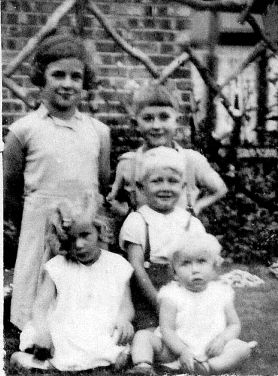

Irene and Arthur were my cousins from Yorkshire. Marjorie and Kathleen lived at St.Annes. The picture was taken in the back garden in St. Annes.

The only time that I went away from home was when we went to stay with Aunt Lucy and Uncle Ernest in Fryston, which was a small pit village in Yorkshire. This was "New Fryston" which distinguished it from Monk Fryston, which is up near Selby.

We went from the L&Y station and I recall the station announcer as she said "Bolton, Bury, Heywood and Rochdale". This was where you had to change to the York train, and this went through the Woodhead Tunnel. It was a big adventure going to Yorkshire. As the train went into the tunnel the lights came on and there was a smell of smoke in the carriage from the engine. We made part of the journey by bus, as the train stopped at Castleford.

Uncle Ernest was the undermanager at the Fryston Main Colliery, and he and his family lived in a pit house in the village that surrounded the pit. No 2 South View was the address, and I can still remember what it looked like. My cousins, Irene and Arthur were older than me, but we had some fun there. Arthur took me into Pontefract to the licorice works where they sold miss-shapes for a shilling a bag. We also visited a park there.

Arthur took me fishing in the Aire and Calder canal, which ran close to their house. I don't remember catching anything there, but we went to Roundhay Park in Leeds and there we caught a couple of tench. When we got them home, Arthur revived them in the bath and they were swimming around. He decided to try and make them swim faster so he put hot water in and it killed them! When they were dead, we shot them to bits with his air gun, propping them up on the back gate. It's funny the things that you remember. We thought that Uncle Ernest was really posh, having a telephone, but it wasn't until a while later that I found out it only went to the pit!! Uncle Ernest took Dad for a look round underground one day, -- talk about a busman's holiday!

When we got back home again from Yorkshire, Ma had a tale to tell us. She had been feeding the flock and was giving them their last feed at night. Our Billy was with her and they went into the big half monitor shed. The fence bordering the backfield was down, due to the farmer's shire horses pushing it over in their quest for grazing. Our grass must have looked better than theirs!! When Ma and Billy were in the shed, the two horses, smelling food, went to the shed door, thinking that they were getting fed. Ma was scared stiff of them and she and Billy were marooned there. It was getting dark when Granddad Foster, finding them missing, went to look for them. He had to shoo the horses away to allow them to get out!

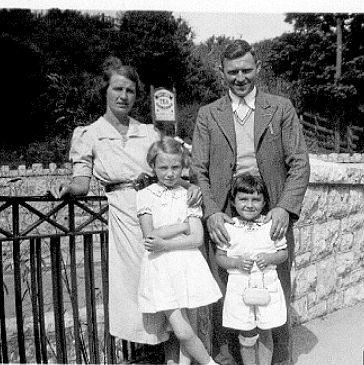

When Edna and Irene were growing up, they always managed to get away for a week during the summer. Ted Twigg was only a surface hand at Baxter Pit but somehow they schemed and saved for that vital break. Their holidays were spent at Old Colwyn in Uchydon Avenue, with a Mrs Newall. or at Bispham. Edna's mum would ask for "apartments" and this meant that you bought your own food and the landlady cooked it for you. It must have been a satisfactory arrangement because it went on for years and allowed them to take a holiday each year, even during the war years.

Edna and Irene with Mum and Dad, Colwyn Bay circa 1937.

Continued...