Park Collieries, 1948 to 1959

The Prototype Anderton Shearer

Ravenhead had two shafts, an upcast, No10 and a downcast, No11. And both of these shafts wound coal. The shafts were all about 700yds deep and added to that the extra depth travelled by the rider, the coal seams were well over 1000yds down. The seams in No10 were the Arley and the Rushy Park. The seam that was being mined when I was there was the Rushy Park, but plans were being made to take the Arley.

You can imagine how the seams dipped towards St Helens, when you think that the Arley or Wigan 5ft as it was known, was only 10yds below the surface at Orrell Road where the M6 cut through it, and yet here in Ravenhead, the same seam was over 1000yds deep. It was a very warm mine to work in, and in No10 pit, before getting on the rider, everybody stripped off to shorts and singlets, even the officials!

We were taken into the Rushy Park seam to watch the "Shearer". This was the original prototype of the machine invented by Jim Anderton, and the forerunner of the same machines that are universally used in most of today's mines, worldwide. It had been made by taking an AB 15 cutter, removing the chain, turning the cutting head on to its side and fitting a drum, this drum was fitted with pick boxes, which held the cutting picks. It was a simple idea, which revolutionized the way that coal was cut and loaded. The drum on the prototype was 15ins in diameter.

The cutter was mounted on an armoured face conveyor of German origin known as a "Panzer." This had been used in German coalmines where a coal plough or "Hobel" was used. The advantage that the panzer had over the Victor conveyor was that the chain was completely captive. Where the Victor had a single chain and flight bars on either side, the panzer flight bar was in the centre of two chains, which ran in grooves at either side of the pan. The pans were fastened together by flexible joints, which allowed the conveyor to be "snaked". This made it possible to move the conveyor across into the new cutting track without having to break it up, as it was with the Victor.

The cutter was hauled along the face by means of a rope, fixed at either end of the face and passing round a "C" wheel under the machine and the cable that powered the machine was carried figure 8 fashion on a cart attached to the machine and dragged along mounted on the panzer, as was the machine.

To create loose ends at either end of the face, headings were cut by using a short wall cutter, and kept in advance of the face. These were necessary to allow the cutting drum access to the next cut. One man operated the cutter whilst his mate coiled the cable or un-coiled it as the machine went along the face. There was a plough fitted at the front of the machine that picked up the loose coal as it came down the face to begin another cutting run. The machine did two cutting runs, exposing 30ins of undercut coal, a man with a drilling machine then followed the cutter, and as he drilled the tops that had been left, the shotfirers charged and fired the coal into the track so that the plough could pick it up on its run down the face.

When the coal was fired, the supports were moved in. These were "Prochar" bars, about 30ins long, with a pin and a hinge arrangement so that they could be linked up to the previous one. They also had a captive wedge fitted so that, once linked up, the dowty prop holding the previous one could be lowered slightly, the linked bar lifted to the roof and the wedge inserted, then when the prop was tightened up again, the newly exposed roof was supported and at the same time, a prop free front was established. In the extracted area, packs were put on as with conventional faces, but they were narrower because the cut was only 30ins wide as were the "prochar" bars.

As the cutter came down on his second run, picking up the blown down coal, the men behind would "snake" the conveyor over into the new track, which had been cleared. This was done by the use of air-powered rams, attached to the side of the conveyor. They were pretty lightweight and could be lifted to the roof by one man, and they had a 2-pronged end to dig into the roof. At the main gate end, 3 jacks together were used to push the drive over, as this also had the weight of the cutter on it.

It was very hot and humid on this face, the heat was oppressive. The men operating the machinery, and the packers, wore nothing but shorts, boots and helmet. In fact, they looked for the entire world like black statues with the sweat and coal dust gleaming on their bodies. Even the deputy and shot-firers wore just a waistcoat and shorts We only had the one visit to this face to see the operation, but some of the lads on the course were placed on this face for all their training, so they had a hard time of it!

After the 6 weeks of training at the training gallery and the pit, we had to take the shotfiring exam. This took place in the mock up heading, where we had to stem a shot in the dummy shot hole. The heading was made of wood and the "shotholes"were in blocks of wood, like a box that could be opened up when the shot had been stemmed to see if it had been done correctly.

We also had to do a practical exam at a pit, and mine was Wood pit in Vista Rd Haydock. We had to go round a working district with the deputy in charge and then compile a report, which was scrutinized by the pit manager. He then questioned us just like he would have done with his own deputies.

We had to take the exam at the St Helens Tech for the M&Q (Mines and Quarries) certificate, this involved reading and identifying gas caps from 1% to 4%, and a hearing test. After this I became a fully qualified deputy and shotfirer, but only able to fire shots, as I was under the age of 25. Uncle John had done me a big favour, putting me on the course whilst I was under age. I had been on the course for about 2 weeks, when Mr. Wright, who was the training officer for the whole of the Wigan area, came into the classroom and said, "I suppose that you are all over 25?" When I said that I wasn't, he said that I shouldn't have been on the course, but to leave it be as I had already done a couple of weeks into it. I was glad about that!!

An Official at Last

We re-started at our own pits again after this, Albert Johnson went straight back as a shot firer, but for Frank Bourhill and myself, we had to do 21 days under the supervision of another official. I went with a chap named Jack Waterworth from Billinge. Jack was one of the old school of officials, he wore riding breeches and long stockings. As I was preparing to leave the pit bottom office the first day on the job, Cliff Green, the Undermanager, said to Jack, "If tha catches 'im wi' moor than one shot rommed, send 'im eawt" That was a good start!!

Detonators in those days were numbered, and each shotfirer was allotted a number so that if any dets were lost, the shotfirer could be traced. The dets were issued from the magazine in an oval tin, fitted with a brass lock, and were in bundles of 10, there were 4 bundles in the tin, and each shotfirer used to check his dets in the pit bottom office, in front of witnesses in case there had been a miscount in the magazine.

I fired my first shot in the Ravine mine, firing for the colliers in the straits there. In those days, the shotfiring cable was cotton covered, and so were the det wires. The outer sheath of the cable came in very handy as bootlaces! The prescribed distance to be from a shot when firing it was 25yds, but when we could, we shortened this, especially on the Yard mine where the usual distance was about 5-10 yds. I've been "peppered" more than once by flying coal!!

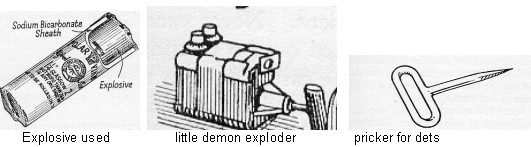

The powder used at that time was made by Nobel in Scotland and was Polar Thames for coal, and Polar Viking for rippings. Occasionally when rock was fired, we used Polar Ajax. All these powders had a sheath of baking soda around them to dampen down any chance of a flash. Later on of course, the sheathing material was incorporated into the powder, when it became known as Eqs or Equal to sheath.

I graduated from the Ravine after my 21 days supervision to a place on the Yard mine face where I had last worked as a driller. There were 4 shot firers to the face and we had 8 men each. I had the bottom end where the return drum was. Each shift, the men carried the powder which was in oval tins of 5lbs, into the district and shot firers would need about 4 tins each for the day's work, surplus powder being returned to the magazine each night. The men were paid 1/6d or 7.5p for each tin carried.

We sat in the gate road while the colliers cleaned up the scuftings and set the sprags, preparing the charges. I had large pockets sewn into my waistcoat, and I made up 8 primers (an 8oz packet of powder with a detonator inside), wrapped the wires round them and placed them in my pockets, this was to speed up the firing process. Sometimes I fired two shots next to one another, especially where two men were "breaking in " together. This occurred when you had a left-hander and a right-hander working alongside each other.

We tied back our cables to 15ft in length, all strictly illegal of course, but a lot handier to work with. Most of the time, we stemmed up with small coal, as there never was enough stemming coming into the district. Usually we would save a piece of stemming in case we got an inspector's visit. The stemming in those days was "green brick" i.e. bricks from the brickworks that hadn't been fired.

After we had fired through the face with the breaking in shots we went back into the gate road and waited until we got a shout from the colliers for the next round. The exploder, a "Little Demon" was basically a small dynamo fitted with gears. The exploder handle, which also had a "pricker"for holing the powder packets, built into it, was used to spin the dynamo. This exploder was carried on the shotfirer's belt.

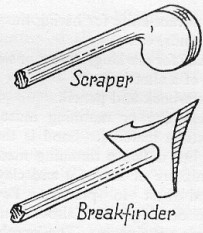

The stemmer and break detector when I first started shotfiring, were combined into one rod made from copper, but later on, the stemmer was separate, being made from wood, the break detector was combined with a scraper, and made from iron. We would get through all the shots by about 12.00 noon, although sometimes we would have to fire "poppers" Short holes drilled in the overhang at the back of the cut that was left on occasionally. These were done with half a packet and a det and made a fair old bang and a smoke!

I recall one incident regarding shotfiring that sticks in my mind. It was on a Saturday morning, and in those days it was coal at any price. We staffed up the face with anybody who turned in, because the NCB had told the workforce that if they turned in for work, that work would be found for them, we couldn't turn them away. The colliers only took 6yds instead of the usual 7.5yds. I wasn't in my usual spot, in fact I was over on the other side of the face, and as the ventilation used to split in the main gate, the airflow was coming in the opposite direction. I had stemmed up a shot for a collier by the name of Danny Towey, we crawled down the face and I turned the firing key. As I did so, I heard the "crump" of the shot and then smelled the smoke as it drifted down the face.

When we returned to the shot Danny said to me "It's done nowt" The shot still looked like it hadn't been fired. Danny set to with the hand pick to pull the coal down, and I went off to fire for someone else. 20 minutes later he crawled down the face to me and gave me the powder packet and det. It hadn't fired! When I had turned the key to fire the shot, another shotfirer had fired at the exact moment, and as I had been used to the smoke going in same direction on the other side of the face I assumed that my shot had fired. It was a lucky escape, because if the shot had found its way on to the belt, and the det had been found, I would have faced prosecution under the Coal Mines Act.

We were working at the start of a new face once, in the yard mine, when an incident occurred. When the new face was being formed out, it was usually by the side of a working face, and a prop and bar track would be made on the flank as the working face advanced and then, the track would be distorted as the weight came on to it. Thus, when the face was ready for development it had to be re-ripped and steel bars set, but at least a track had been formed to work in.

We were on such a face and it had been re-ripped, barred up, and the belts installed. In mining, there are the terms "Back abutment pressure" and "forward abutment pressure" In real terms, it means that when ground is excavated, breaks occur in the strata on either side of the excavation, so that when a face was ready to move forward, some weight was expected on the supports about 5-6yds forward.

We had taken about 6x5ft cuts from the face, and as we were cleaning up at the end of the shift, we heard the props begin to creak. Slowly, the props were being pushed into the floor by the weight of the overburden!! I was the official in charge on that section of the face, so I told the men to leave off what they were doing and get off the face. We stood in the roadway and watched the props slowly disappear into the floor, and the face just closed up!! It had to be re-ripped again before work could carry on.

Another shotfiring incident that springs to my mind is one that happened in the Ravine tunnel. During the dayshift, there had been a runaway and about 6 bars had been dislodged. A big piece of rock had fallen out of the roof and was across the track, blocking it. I was sent along with some men to clear the obstruction and re-set the fallen timber. We had no means of drilling a hole in the rock to fire a shot in it, so I told the men to go out of the way, and I made up a shot which I placed on top of the rock, I covered this with a couple of spadesful of mud, and I fired it. I had read somewhere that the explosive expanded all round when fired and when I got back to the scene, the lump of rock was in small pieces. It definitely saved a lot of sweat that day!

Afternoon Shift with the Rippers

It was 1954 and Edna and I had been married for about 2 months. I couldn't get up in the morning and as a result I overslept on a number of occasions. Finally I decided to try the afternoon shift for a while. As it was, we had one week in four in the afternoons to fire for the rippers, and I asked my mates if they minded me taking the afternoon shift regular. They thought that I was mad!! The outcome was that I spent the next 3 years working the back shift. I wasn't a boozer so it didn't worry me about not going to the pub. I didn't see a lot of television, which was in its infancy then, and in black and white, but other than that I enjoyed my time on the back shift.

We started at 2.30pm so I only started out for work at 1.30pm. I got a lot of work done on the house, such as painting and pointing, and I never seemed to be tired. Another plus was that no one bothered you; inspectors rarely came to visit the pit on afternoons. My mate on afternoons was a fireman by the name of Moses Hughes. Mo had been a collier in the Ravine mine with Bill Cunliffe as his drawer. Both of them had been on the course after me. Mo had Welsh ancestors who had originated from Cemmaes Bay on Anglesey.

He lived in Stubshaw Cross, which was known as "Little Wales". It even had a Welsh chapel with a notice board in Welsh. Mo was a typical Celt and had a fiery temper. We used to bring coffee in a flask for our afternoon break, Mo carried his flask in an inside pocket of his waistcoat, and one day, as he struggled to reach the telephone, clambering over some tubs, the flask dropped out of his pocket and smashed on the floor. He booted the flask up and down the level!! It was so funny to watch.

There was one incident that happened to Mo. It was during the spell that I had in the dayshift, so I wasn't with him at the time. Mo was travelling down the face, on his final examination of the day. He saw a prop in the waste, holding up the roof and preventing it from coming down, so he decided to knock it out, using a piece of 2ins pipe.

As he struck the prop, the waste collapsed, the pipe flew up and hit him in the jaw, breaking it. He had to have his jaws wired together for 6 weeks, and as he had false teeth, the wires had to be put through his gums. It must have been pretty painful. He told me about it, and he said that the worst things that could happen were trying not to yawn, and drinking a pint of Guinness with a straw!!

The telephone system those days was pretty primitive. All the phones were in series from the pit bottom, and were all interconnected. To call on them, there was a handle, which you turned, this rang the bell. The mouthpiece was built into the body of the apparatus and the earpiece was on a hook to be lifted off. When the undermanager wanted to contact the face, he would ring the bell and the man at the face would answer. If anyone else had to be contacted, a station signal was rung on the haulage signals, otherwise when the phone rang at any of the transfer points, it was ignored.

There was one transfer point operator by the name of Bob Benson, an inoffensive little chap, who, being bored by just sitting there watching the coal go by, liked to eavesdrop on conversations. I was in the office one day, when Cliff Green was trying to contact the face. Bob was listening in as usual, and Cliff, who couldn't hear the face man because of the noise from Bob's transfer point said "Put t'phone deawn Bob" and Bob, being startled said "Ahm not listening"!

I recall that when Mo was on the phone, he didn't seem to realize that the mouthpiece was on the box, and if he wanted to say something that he didn't want the caller to hear, he would put the earpiece to his chest, thinking that this would muffle his voice!!

I used to fire the rippings, and sometimes would go out of the Yard mine and into the Ravine to use up any surplus dets that I had. I went into the Ravine one day and I had stemmed up two shots. I fired one and when I tried to fire the next, but it wouldn't go. I had to dig it out, and when I did, I found that the first shot had flattened the det in the second shot, making it incapable of being fired. Blind panic then set in! What can I do with it? I know, I'll take it home. I only found out later that the best way to get rid of duds was to make a hole at the other end of a new charge, stick the dud in and fire it off. It lay in a drawer at home for quite a while, and then I had an idea, I took it into the pen, lit some petrol soaked rag in a tin, dropped the det. in and retired quickly. It blew the tin about 2ft in the air!!

The Yard mine at that time had a front rip and a back rip. The back rip was about 30yds to the rear of the face, and it was decided to catch this up with the face and then one team could carry out all the operation. The men employed to do it were Bill Tracy and Fred Naylor. They worked hard to achieve it, no doubt spurred on by the piecework rates that they were paid.

Bill was one of the original Lyme pits men who had driven the access tunnel, and had been the face "bummer" for a while. He was a wizard with a spade, not very tall and very muscular. He left the industry whilst I was at Stone's, to work for the parish priest in Haydock somewhere, as a gardener, and died in his 40s from spinal cancer.

Fred Naylor was the son of old Phil, and stepbrother to Jack, or Ack, as he was known. The Naylor family was all employed at Stone's, Phil and Jack worked together as collier and drawer in the Ravine, typical old style pitmen. Jack never married, and he and his father spent their wages on ale and horses. It was said that when one of Jack's sisters was pregnant, Jack, in all innocence said to her "Tha wants thi clogs 'eelin', th'art walkin' backerts" When the baths opened, it made no difference to them, they still went home dirty and just washed to the waist every day! Fred had another brother, Jimmy who worked as a collier on one of the faces and he married one of the girls off the pit brow, Hetty Foster..

There was one incident that changed Fred's life completely. He had two mates in Downall Green, where he lived, and one day he let them borrow his motorbike. They crashed into a wall and were both killed outright. Whether Fred blamed himself for the accident I don't know, but he got very depressed, and had to undergo electric shock treatment in the psychiatric department at Billinge hospital. He worked on and off after this but his whole personality had changed. He was working at Parkside when I was there, and he died around 1980, still quite young, in his early 50s.

The main gate team at the time was, Albert Klavins, a Latvian, Tadeuz Filipek, a Pole, Joe Mychalczuk, a Ukrainian, and two Englishmen, Cliff Houghton and Charlie Pearce. Cliff had been a driller with me and Charlie used to be a window cleaner in Ashton. Albert was a big lad; he could carry 11x12x9 arches, one piece at a time on his shoulder.

The team evolved a system of support for the main gate involving 6 sets of hardwood chocks and 7 8x6 RSJs. On each side were 2 carrying girders, one fast and the other loose, which the chocks supported. As the front rip was fired and shifted, the 2 loose carriers were moved forward and an RSJ placed across them to support the exposed roof, this gave a prop free front so that the cutter could traverse the heading.

The 2 carriers were then wedged tight to the chocks, thus pinning the RSJ to the roof. At the same time they were holding the previously set ones as well. As the back rip was prepared for firing, the other set of carriers were loosened and moved forward, freeing the cross girder under the back rip. Each day the exercise was repeated, the chocks having quick releasers built into them to facilitate the process of moving them forward. It worked so well that teams of rippers from other pits came to look at the operation.

Albert was in charge of the whole job. 14yds of pack were put on either side of the heading, 6 yds from the wastes and the rest from the front rip, the whole of the back rip being filled out on to the belt. Before Albert dropped the back rip, he would lay props across the belt and put sheets down where the arch legs would go, to avoid having to fill it out. When I had fired the 5 shots in the rip, Albert would stand astride the belt, pick in hand, dragging the props out one at a time to free the dirt and send it on its way. They were a good team of men and could be finished for 8.30pm. Some pits would let their pieceworkers go home when they had finished the job, but not Cliff Green, his excuse was that "they'll not do a proper job".

I recall one incident with Albert. It was one holiday time, and I used to work the holidays, so that I could take them when my father-in-law was off work. I was with Albert and some more men doing a job. We used to do any job that couldn't be done when the pit was working. It was break time and we were "having a minute", lying down with the cap lamps out.

There were quite a lot of mice at Stone's, a relic of the days when the ponies were underground. We were keeping quite still, and the mice came out, foraging for food. We had hung a bread crust on a piece of cap wire, suspended from the arch, and we could see what was going on by the light of the lights in the roadway. The bread was just too high for the mouse to reach, and it was on its back legs trying to reach up for it. Suddenly, another mouse appeared, and, leaping on to the back of the first one, made a grab for the crust. It then held on, swinging to and fro, eating it. The first mouse then started to eat the crumbs that were dropping. If I hadn't seen it with my own eyes, I wouldn't have believed it!

We had, at that time, some lads coming up as trainees, I recall two of them, one was Arthur Speakman, the brother to "Snoek" who lost his pants on the surface picking belt. Arthur was working with the rippers on the top road, and he was very timid. The drillers were on the face at the time and as Arthur was spading dirt, one of them threw a bit of dirt on to Arthur's helmet. He looked up, startled, thinking that the roof was falling in. He then moved across to the other side, to work from there. The drillers followed him and threw a bit more dirt, Arthur said, "Ah'm shiftin' away from 'ere it's not safe" The drillers were killing themselves laughing!

Arthur found out that he get up pit early by having a headache. Mo and I used to wait for him to come to us, wearing a sad expression and complaining about his head hurting. He couldn't see that all that he was doing was making himself short of money, as his time was stopped from when he left the district.

Another trainee was Ken Thompson also known as "flocks". This was from his expression "get in the flocks" i.e. bed. I don't think that Ken was cut out to be a pitman. He was put with little Bob Shaw, who had a pack in the lower side of the heading. Bob was thinking to himself that he now had a helper. Kenny came to him and said, "Are tha trainin' me?" Bob said "Aye" "Well" said Ken, "Ah'll sit 'ere an' watch thi workin'" Bob didn't know that he was only having a bit of fun!

Those days, we had two overmen on back shift, Bill Heppinstall or "Bill Emp" as he was known, on afternoon shift and Bert Heaton on nights. I didn't have a lot of dealings with Bert, but old Bill was a real character. He had bad eyes, and wore glasses with very thick lenses. He always wore riding breeches and long stockings, and having bandy legs, looked really comical. The tobacco that he chewed was called "aromatic", I can smell it now. He always had a good supply in his tobacco tin, and he wasn't skinny with it, if you needed a chew you could have one from old Bill.

He would come on shift as early as 12.00 noon, and was only off home at midnight, a real dedicated man of the old school. His time was split between both shafts, and he would go down one until snap time, come up for his break, and then travel the other one, taking in all that was going on with the different jobs.

He had two favourite expressions " Ma boss sez" and " Promise um owt fer t'get job done, but doan't pay um. They'll uv fergetten abeawt it in a fortnit" Meaning that as the men were paid a week in hand, they wouldn't remember what had been promised when the job was done.

At that time, Tony McNamara was drilling on the face. He was Tom's son and he had as a mate, a lad by the name of Jack Simm. Every day, as they came down pit at 9:00am, they would go into the pit bottom office before going into the far end. It was sometimes to get new drilling bits which Cliff kept locked up in a cupboard, and sometimes it was just to pass a bit of time on.

One day, when they were there, No one was in and Jack was reading Cliff's instruction book in which he used to leave word on any jobs to be done by the back shifts. He said to Tony, "Isn't his writing lousy?" Cliff wasn't a good writer by any means and at the best it could be described as a "scrawl" Jack said, "I'll leave him a message" so he wrote in the book " Wrighting shocking." When Cliff saw this he said "has t'seen this, 'e cawnt spell!" Cliff then wrote underneath it "Spelling putrid"!

He said to the other officials who were in the cabin, "Ah'll find eawt who wrote it" Of course he had a good idea who it was, and it was a matter of proving it. One day, as Cliff was going along the face, he came across Jack and Tony, sat in the heading, waiting for the colliers to shift some coal. He said to them "Are yo' lot any good at spellin'?" "Aye, we're not bad at it" came the reply. He got out a piece of chalk and on a piece of conveyor belt he had them spelling out different words. He then said to Jack "con t'spell writing?" "O'course ah con" said Jack, who promptly spelled it out "Wrighting." "Neh ah've getten thi" said Cliff "It wus thee wot wrote in t' book. Keep eawt o' theer in t'future!"

As I said earlier, belt riding was forbidden in those days, but that wasn't say that it didn't go on. After all, it's a lot easier to hitch a ride than walk up a 1 in 3 incline. In the back shifts I think that more or less everybody did it. There are a couple of good tales to be told about belt riding, one concerns Harry Barrow, who was a fireman on the Yard mine. Harry had jumped on the belt and was kneeling. As he approached a small bridge, he didn't get down far enough, and the bridge, which consisted of two boards nailed together and placed on brick pillars, was picked up by him on his back, and carried up the tunnel. It was a really funny sight! One of the workmen said "Harry favvered an aeroplane gooin' up t'belt."

Another time, we were waiting to go underground on the afternoon shift, when one of the day men, Tommy Welding came up with two black eyes and a swollen nose. "What's done?" someone said. "I've run in a cable at t'bottom ut t'brew" Everyone was sympathetic, and said that cables shouldn't be left hanging like that. We thought no more of it until I was coming out at the shift end. As I jumped on to the belt at the bottom of the tunnel, I had to duck quickly to avoid a girder, which had been set across the roadway to accommodate a warrick. It was set at a sufficient height to allow walking underneath it but not for belt riding! "Yes," I thought "and now I know where Tommy got his black eyes".

We had, working on the afternoon shift, a big, fat, lazy Yorkshireman by the name of Geoff Handley. He came to Stone's as a trained face man, but whoever trained him didn't do a very good job! When we were short-handed he was put on to the face. I hate to put a man down, but he was completely useless. I suppose that in today's climate he would have been fired off in no time at all.

He was once sent to the middle road of the face to make up a team. None of the regular crew was working so both men were spares. As I have said previously, the 10ft bar was set before all the dirt was shifted otherwise there was nowhere to set the jackleg. When Mo Hughes and I were on our last inspection, we came into the roadway to find that all the dirt had been packed and Geoff and his mate were stood on tiptoe trying to set the bar! We left them to it, and I still don't know how that bar got set finally!

One day, when he was sent to work as spare man with the main gate rippers, he was put in the higher side pack area. It was a long pack of 14yds, so the dirt from the main gate had to be "cast" i.e. turned from man to man, using shovels. Handley was placed in the middle between two regular men. The result was that the man casting to Handley had a huge pile of dirt in front of him and the man putting the pack on was waiting. Handley said "Why don't we build a wall rahnd this dirt then we'll not need t'shift it." He was one of the laziest of men that I ever came across!

He was a misfit and matters came to a head one afternoon. He was working with the main gate men again, and Mo was in a paddy about something, as he was on occasion, being a fiery tempered little so and so. Mo said something about not paying somebody, and Handley said, "Tha'll pay me". This then developed into a slanging match, with Handley calling Mo a "little Welsh bastard" To which Mo replied "Well, tha'rt a fat bellied bastard" In hindsight Mo should have kept his mouth shut, but he just couldn't.

Handley picked Mo up and literally threw him under the ripping lip and into the pack area. Mo's face was ashen! He said to Handley "Get up t'pit"! Handley went out muttering threats "Ah'll wait fer thee on t'top." As we were going on our final inspection, Mo said to me "Dust think he will be waiting?" Anyway he wasn't and Mo had to put it in his report that he had sent him out. The outcome was that Handley was sent on regular nights in No 2 pit, and he left the industry soon afterwards. In those days it was virtually impossible to sack anyone, it was ridiculous really, but a job in the pit was a job for life. The government wanted coal at any price.

This attitude meant that men could have time off and not get penalised, except that they lost their attendance bonus, and even that could be saved by getting a doctor's note which at that time cost one shilling. It was said that Dr. McCurdy who had a surgery in Ashton, once asked a man who wanted a sick note. "Why do you need this?" And the man told him that it would save his bonus of 30shillings. "Right" said the doctor, "The price of notes has gone up to half a crown, I am having some benefit too" He reckoned that the sick notes paid for petrol! I recall going to the doctors myself when I was ill for a day and being asked, "Do you want a miners Monday paper?"

The men could come in at weekend and they had to be found work. They were paid at time and a half for Saturday morning and double time from midday through to midnight Sunday. We as officials got nothing. Our basic wage was quite good for a 5-day week, it was £14.00 at the time, and we were paid for any sick time that we were off, up to 6weeks in a year.

I've seen men come to work on a Saturday afternoon and been found work cleaning spillage. They had no intention of working, just coming to be paid. They would dig holes in the spillage and lie down in them to go to sleep until the end of the shift. I reckon that Sunday was the worst "skiving" shift of all. It was on a Sunday that the main belts were re-hinged, and any work in both fitting and electrical departments was done. Also pumping was carried out, especially from the Ravine mine where water was a problem. We had a pump man in the Ravine who was getting on in years, but was still greedy for overtime. He would screw down the outlet valve so as to restrict the water, because it had been agreed that once the water had been shifted, we could go home. He would make sure that it lasted the full 8 hours! One day a mate of mine, another deputy, followed him and opened up the valve, but Tommy went back and closed it down again.

At that time it wasn't necessary to operate a full 24 hours cover, as we had no forcing fans in operation. As long as the water was under control we could leave the colliery unattended at the weekend. At the bottom of the Ravine tunnel was a worked out area, which had been known as the "Hall pillars". This name came from the fact that it had been a pillar of coal, which had been left originally to protect the mansion of Lord Gerard, known as Gerard Hall. This hall had been demolished in the 1930s. As Lord Gerard was owner of the coal royalties, J&R Stone the owners of the colliery had to leave the coal under the house or the place would have collapsed through subsidence. After the house had gone, the coal was extracted.

I had heard my dad talking at home about "T'hall pillars", when I was a child, but it was only when I started working at the pit that I realised what they were. The whole area was worked out prior to Nationalization in 1947, but the make of water from the old working was quite substantial, and had to be pumped out to the pit bottom and then up the shaft. There was a lodge hole some hundred yards inbye from the make of water, and the gully that the water ran down was just like a small stream. The smell from the water was terrible, like "rotten eggs" due to the acid in the water coming in contact with iron pyrites and other minerals.

The lodge hole that the water ran into was quite large, about 30yds long and made from 11x12x9 arches. This would fill in 12hours, so if pumping stopped at 8:00pm on the Saturday the water was just getting to the top when the day shift arrived on Sunday dayshift. This gave us Saturday night off. The system worked ok until one deputy went home early and the dayshift arrived to find the pumps under water. Uncle John or JB as he was universally known, was understandably furious. We had to give the pumps 24hour cover.

I recall, one Saturday night being in charge. My pumper was a lad by the name of Stan Adamson. We decided to start the pumps and then go into the return road where it was a bit warmer, to get our heads down for an hour or two, after all, there was nothing else to do. According to the Coal Mines Act it was forbidden to sleep underground but the pitmen that didn't do it at sometime were few and far between.

Stan used to like Guinness and would have been to the club before coming to work. The Guinness would start to work, and Stan would say "I'm just gooin' t'bury some nails" Which of course meant that he was going off along the return, finding a suitable spot for a makeshift toilet, digging a hole and relieving himself. Anyway, we started the pumps this night, made sure that the ammeter was reading the right amount of current, and departed for the "sleep zone".

I awoke about 5:00am and made my way to the pumphouse. I was scared to death!! There was a blue haze in the pumphouse and the pumps were very hot to the touch. I switched them off, opened the "pet" taps to allow some water in and nothing came out except pure steam! I could see my future as a deputy draining away with the pump water. Gradually, the pumps cooled down, and Stan, who by this time had wakened up, came to see what was wrong. We switched on again, slowly opened the valve, and, success!! The pumps were working again. No one ever heard of this escapade, but on future occasions, the pumps were checked regularly and I couldn't get to sleep much after that.

Continued...